Since 2014, a few friends and I have been mentoring a group of teenagers aged between 14 and 18 who live in rental flats in Lengkok Bahru. They were introduced to us by Beyond Social Service (BSS), a social service provider. These teenagers are not your average Singaporean teenagers. They cannot be, for they live in public rental housing in a country with one of the world’s highest home ownership rates. These teens grew up in circumstances that professional, middle-class, and often privileged volunteers like myself did not. Yet, they demonstrated to me immense maturity, not only in negotiating hurdles in life but also in appraising the situation they are in. During one of the casual discussions I had with Danny, one of the teenagers I met in programme, he had this to say:

“All kids have talent. It’s just that some of them have not been given the opportunity to develop or showcase their talents.”

The issue of social inequality in Singapore is not exactly new, but it has gained momentum in recent years. The 2014/15 S R Nathan Fellow for the Study of Singapore, Mr Ho Kwon Ping, said in his final lecture that class boundaries may have ossified to the extent that they severely limit social mobility. The results of a large-scale survey study by NUS Sociology Professor Tan Ern Ser seem to confirm this. Prof. Tan explains in his recent paper that upward mobility chances decline when moving down the social ladder. For instance, while 60 per cent of fathers with a polytechnic diploma are likely to have children who obtained degree qualifications, the comparative figure for fathers with primary-level education is 12 per cent.

To put it simply, the less educated you are, the less likely that your children will surpass your education level. This reality is stark for those with less means because educational achievement is seen as the most viable way up the social ladder. This problem has not escaped the attention of the government, which has attempted to remedy inequalities through various ways. Whether the policies have worked is a subject for another article altogether but the point here is that Singapore’s much-vaunted meritocracy is an ailing system and it is tough for those at the bottom to get opportunities to move up.

Social Capital, Networks and Empowerment

Various sociological studies have pointed to the importance of social networks in facilitating social mobility or maintaining class status. Sociologist Pierre Bourdieu refers to this mechanism as social capital, or networks that an individual can tap for personal gain. Network theorist Mark Granovetter elaborates that it isn’t any form of networks but ‘weak ties’ that helps one move up the social ladder. Moreover, both scholars emphasise that not all networks are equal. All over the world, it has been found that affiliation to certain organisations, occupations, schools or racial groups provide more network advantages than others. More often than not, these networks structure opportunities. Linking this back to Danny’s remark above, even if a young person has immense talent in poetry for example, it is unlikely that his or her potential will be maximised if it is not matched to necessary support and training. This was the case with the Lengkok Bahru teens. They were driven and showed promise in various aspects, there were some issues:

- They lacked the confidence to speak out or even articulate their aspirations.

- They lacked the know-how to accomplish some of their aspirations.

- They did not know anyone who would be able to help them work towards accomplishing their aspirations.

For example, the teens struggled with tasks that we took for granted, such as compiling a portfolio for applying to certain schools or programmes. My two friends, Shamil and Danielle, and I thus reinvented ourselves as Kopitiam Lengkok Bahru (KLB) and designed an ambitious programme that aimed to help the teens become more confident and realise the importance of networks. We styled ourselves as nodes in these networks, which the teens could tap for knowledge and connections.

We used the arts — photography, poetry, drama, dance — as the medium to deliver our lessons because it was what the nine teenaged participants were most enthusiastic about when we discussed with them the structure of the programme. Our first step to exposing the participants to networks was to introduce them to online crowdsourcing. The KLB used this channel to reach out to experts in drama, photography and dance, to ask if they would volunteer their time to teach the teens. We had hoped that the teens would learn the importance of cultivating ties with people, especially people who they would not usually interact with.

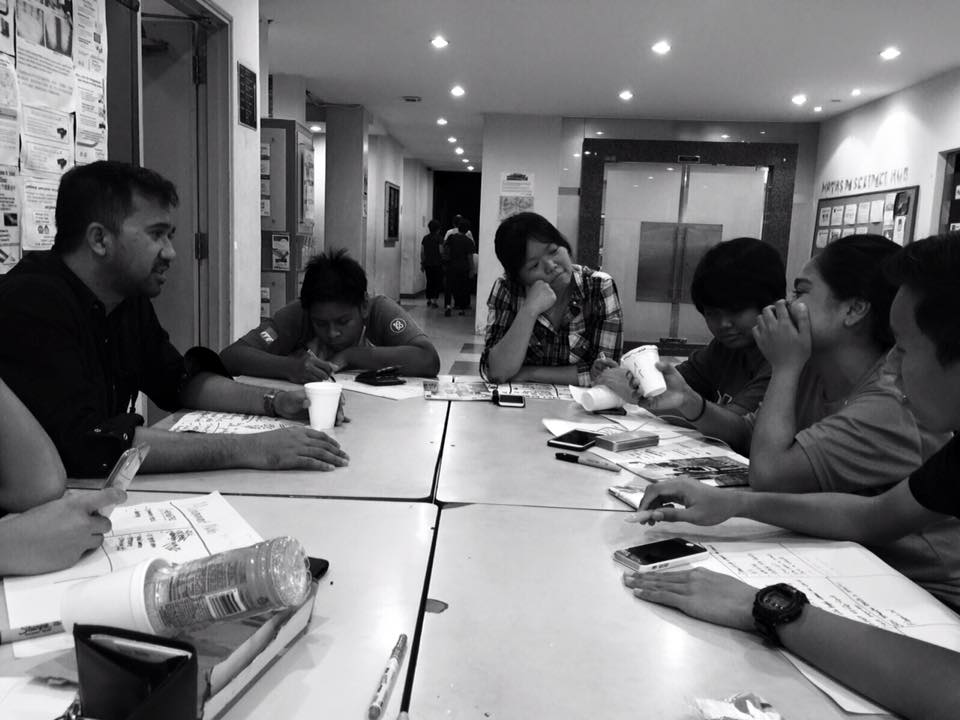

Photo: From Kopitiam Kengkok Bahru’s Facebook Event: In the Interim

This was easier said than done because the teenagers were really shy. It took many hours of interaction before the teenagers opened up to us and the experts. Shamil, Danielle and I continued to press for their active participation in planning the programme, and collectively, we set a major target, which was to organise a public photo exhibition showcasing their photographs about life in Lengkok Bahru.

Months of toiling culminated in two gallery exhibitions. The lead-up to the first exhibition at SCAPE wasn’t smooth but once it was up and running, the reception from the public was tremendous. The greatest satisfaction for us, was to see the shy teenagers stand in front of their work and speak to the gallery visitors about life in public rental housing while explaining the significance of their photos. Some of them were also put on stage for an artist question-and-answer session at the opening of their second exhibition at Artistry Cafe. For some of them, it was the first time they had ever been on stage and they said that they learnt a lot from the experience.

Since then, other opportunities have come up as a result of the media coverage of KLB. People from the drama group Drama Box came to interview the teenagers and ask if they were interested to be part of a project. A photography group from Korea expressed interest in collaborating with KLB. In September, Yale-NUS College invited the volunteers to speak at a seminar for their students. One of the teenagers in the programme, Asnur, even secured his own photo exhibition at Marina Bay Sands, due to the exposure he received from the first exhibition.

Experimenting for the future

Asked to evaluate the outcome of the programme, I would say we achieved our objective, since the initial goal was to connect the teens to new people to expand their networks. For the long term though, how can we continue to help them engineer opportunities, so they can get to a stage where they can do so on their own?

One question we had was whether such an approach, if applied to other needy or disadvantaged groups, could help reduce class inequality in future. We don’t have the answer to that. But my belief is that having more of such value-motivated and driven volunteer collectives working in concert can effect change. There are other similarly loose collectives made up of volunteers, which have so much to contribute to society. Perhaps, it would be worthwhile for the relevant ministries to pay attention to these disparate, independently run programmes and involve them in conversations relating to policy.

What would be helpful is for there to be a rigorous measurement of the effectiveness of such programmes. We can then see how to improve them. There have been precedents set elsewhere. Mincome in Canada and the Moving to Opportunity programme in the US are great examples of how governments have invested in experimentation to seek optimal solutions for reducing income inequality. No doubt, these experiments were very structured and had their shortcomings, but they aided in grounding policy decisions to what actually worked, as opposed to relying on shaky, ex post facto determinations of policy success or worse still, grand ideological colloquies. Governments that sanctioned these “randomised experiments” made the data publicly available for all interested parties to analyse. Consequently, it enriched the discussion with many different perspectives on these specific issues.

Personally, I envision a future where a conglomerate made up of well networked volunteers discuss values, exchange ideas, come up with testable solutions and most important of all, change lives. Although working outside of government purview, these organisations should seek its support, along with the support of philanthropic organisations and private corporations.

But before we move on to this, it is imperative that the nation take a step back and start asking the difficult questions on meritocracy and inequality. This is not so that we can make those with means feel uncomfortable. It is so that as a nation, we can acknowledge the deep-rooted problems and hopefully distribute those means to create a more equal and just society.

Mohammad Khamsya Bin Khidzer is a doctoral candidate in the Department of Sociology at the University of Illinois Urbana Champaign. His research interests are in the areas of transnational studies, race relations, social networks and community empowerment. He was formerly a Research Assistant in the Society and Identity Cluster at the Institute of Policy Studies.

Mohammad Khamsya Bin Khidzer is also featured on The Future of Us Ideas Bank Page (Dreamers)

Top photo from Below Social Services Facebook Page