IPS Commons will periodically upload speeches that may inform public policy discussion in Singapore.

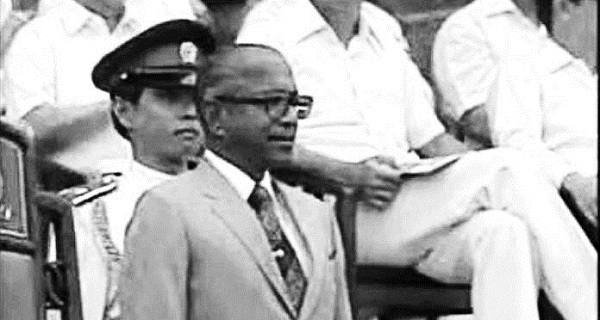

The following is a speech by President Devan Nair, at the Harvard Club of Singapore’s Annual Dinner at the Mandarin Ballroom South Wing, on Monday, 31 January 1983.

BREAD IS BEAUTIFUL

I accepted this invitation with some trepidation. It was the same trepidation with which I had once accepted an invitation to address the annual gathering of the University of Singapore Economics Society. I knew that at least some of the economists present would expect me to display my ignorance in some arcane field of economics, which was their special preserve.

I managed to overcome that hurdle. The title of my address was, “The Non-Economic Objectives of Economic Growth”. It is a subject which most economists do not think about.

My instincts proved right. I was not torn to shreds. In fact, I felt as safe and secure as a lion in a den of Daniels. I would like to feel equally safe tonight before this gathering of the Harvard Club in Singapore. For to speak without knowledge, or only a half-ripe knowledge, would be foolhardy. To do so without conviction would be hypocrisy. I have therefore chosen to speak on a topic which does not demand deep or wide erudition. The conviction may be unfounded. All that can be claimed is that it is, nonetheless, real. My prosaic title is: “Bread is Beautiful”. I ask you to bear with me for a while, before the significance I give to the title is made clear.

The on-going public discussion on the need for moral education indicates the keen sense of a lacuna in a society pre-occupied with the pressures of material production and well-being. Indeed, at least some letters to the press reveal a tendency to go to the other extreme, and to regard material values as a source of unmitigated evil.

The dichotomy between matter and spirit is not new to philosophy. Proponents of both have either ignored or abused each other through the ages. For most people, however, the cleavage exists only in the dogma, and not in reality. It is often forgotten that polar extremities rotate at the opposite ends of the same axis.

I count myself among those who have come to discern, in both public and private life, a rigorous equation between individual and group performance, and the values, beliefs and standards espoused by the individual and the group. Poor motivations and standards invariably lead to a poverty of performance and results.

In the course of my public life, I have come to judge individuals not merely by their paper qualifications, however estimable these may be, but also by the intangible qualities of mind and heart, and the capacity for the commitment to individual and group goals which exceed purely selfish personal ends.

What bind individuals together in family, society and nation are qualitative and moral factors. Behind an excellent material product there are no doubt excellent machines. But behind excellent machines there must be men and women, excellent in more ways than one. Where then, I have often asked myself, is the fundamental cleavage between matter and spirit, which the schools of philosophy prate about? In truth, I believe there is none, and I hope to share with you some personal reflections on the subject.

Social criticism has its polar opposites. At one extreme, we have those for whom material affluence, and the mastery of the material and technical means of such affluence, are the be-all and the end-all of human existence. For them art, music, literature, religion and philosophy are mere frippery and moonshine. At best, art is a commodity among other commodities, and judged more for its economic rather than its intrinsic value.

Do things like art and philosophy contribute to GDP growth? How do music and poetry, for example, help to increase one’s bank balance? Therefore, dismiss these things. Philosophers, however brilliant they may be, are notoriously incapable of baking bread. So, why bother with them. The only philosophies which interest this group are those of economics and science, or what are called the growth-oriented philosophies.

When one looks at the pervasive poverty, squalor, and disorder of several developing countries, in particular the non-oil producing ones, one is tempted to concede that the spiritual appetites of men have been singularly unproductive of the utilities of civilised life, that would include decent homes, good schools and universities, hospitals, decent clothes, clean potable water and wholesome food. All these are possible only in the context of high industrial and agricultural productivity based on wealth-generating knowledge and skills.

We may describe those who swear by the primacy of wealth-generation as persons who subscribe to the materialist affirmation of life, quite exclusive of the things of the spirit.

At the other extreme we have what may be described as the ascetic denial of life. The hero of this culture is the world-shunning ascetic. For him, the world is an unredeemable vale of tears, and the sole solution an escape into some extra-cosmic cessation or transcendence. At best, life on earth has merit merely as a stepping stone to the beatitudes of the beyond. And if you happen to like some of the so-called wicked things of life, there are those who would caution you about the prospect of an eternal roasting in the infernal nether regions of the after-life.

Yet others in this school denounce the preoccupation with material pursuits as demeaning and soulless. The flamboyant exhibitionism of some businessmen who spend lavishly in expensive restaurants, hoping to impress those less favoured by Dame Fortune, came in for severe strictures recently, and quite rightly so.

There is, however, a snobbery in the reverse which is equally deplorable, that of the artistic and literary Brahmins who look down their aristocratic spiritual noses at coarse materialistic untouchables who excel only in the art and craft of money-making.

I have perhaps painted with all too brief and quick strokes the salient characteristic of the two mutually exclusive extremes – the materialist affirmation of the life and the ascetic denial of it. Volumes have been written upholding the one exclusive extreme or the other. The bourgeois and the bohemian are supposed to live in separate closed worlds of their own.

Obviously, there are varying shades and degrees in between. For instance, there are those who would please both God and Mammon. For good utilitarian reasons they ensure that their bank balances remain healthy. But they also take care to insure themselves, through ritual observances and the like, against risks in the unknowable Beyond, into which we shall all pass one day. But here as elsewhere, sweeping generalisations merely mislead, as there are countless others who worship with deep faith and devotion. It is a safe guess that both they and the world are immeasurably better off as a result.

A balanced approach would be suspicious of the exclusive polar opposites. A too trenchant dichotomy between material and spiritual values serves neither the cause of life nor of truth. It impoverishes the one, and diminishes and distorts the other.

Indeed, as one surveys societies and their social, economic and cultural histories, one suspects that there is no fundamental dichotomy at all. The cleavage is more fiction than fact. For in actual life, material and spiritual values inter-penetrate each other. There is an immixture of both at all levels. Distortions in perception and conduct occur only when the immixture is unequal or unbalanced, with one tendency attempting, not very successfully, to overwhelm and smother the other. This is probably what the ancient Chinese meant when they said that sound mental and physical health was the result of the Yin and Yang being in balance.

This immixture of material and spiritual values becomes evident when one attempts to assess the quality of everyday life, in homes, offices, factories, fields, schools and hospitals, among other places. One discovers that it is the quality of the human beings concerned, their motivations, aspirations, and the standards which they set for themselves, which determine the quality of their work, of working life and of human relations generally. It makes all the difference, for instances, between penury and productivity, between smut and sublimity.

You can programme robots and computers for successful performance, without inputs of Shakespeare and the saints, or of art and music. But human beings are differently programmed, for the good reason that they have not only physical and material appetites to assuage. Call it what you like, but there are also nameless and unappeasable hungers of mind and spirit. The artistic and literary creations and traditions of mankind bear constant witness to these human aspirations through the ages. And they return after every banishment, as they clearly help men’s otherwise drab and ignorant lives to waken to beauty, wonder and joy. Indeed, most of us are not strangers to ideas that haunt us with their radiant tread. Or as poet Keats put it,

“…… solitary thinkings such as dodge

Conception to the very bourne of heaven,

Then leave the naked brain.”

Honest scientists and enlightened men of the spirit occupy common ground in at least one respect. They both concede that reality is mind-bogglingly complex; and quite unamenable to confinement in any single trenchant formula. At the frontiers of exploration, whether in physics, biology or psychology, seekers peer into fathomless infinite which philosophers in classical times referred to as “The Mysterium Tremandum”. Little wonder then that expanding knowledge and the growing light of wisdom have for travelling companion an increasing humility. And even less wonder that bigotry, dogmatism, intolerance and fanaticism should have, as their common fount and province, the dark fields of ignorance.

Mutually exclusive philosophies are fruitful sources of fallacy in life, thought and action. For example, the pursuit of moral and spiritual values should not blind us to the enormous significance and utility of science and technology, in terms of satisfying the essential foundation for an improving quality of life.

One would far rather meditate, for instance, and more fruitfully, ensconced in a comfortable modern armchair, than in a germ-ridden hovel. And it is with wry amusement that we regard philosophers and politicians who denounce materialism while seated in well-lighted air-conditioned studies and offices. One might also legitimately wonder how may poems extolling the sublimities of the spirit are written with silver and gold-plated fountain pens.

As I was writing this, I discovered I was in distinguished company. I came across one of the recent Reith lectures by Dr Dennis Donoghue, published in “The Listener”. I quote Dr Donoghue:

“You can hardly play an electric guitar and maintain an aesthetic objection to technology. Besides, artists have discovered that there are constructive possibilities in the new mechanisms: electronic music, tape, digital recordings, video, inter-media of many kinds. The reception of the Arts is now technologically through and through; Zeffirelli’s production of La Boheme on television, Brideshead Revisited as the book of the television series.”

We impoverish ourselves if we allow the world of business, science and technology to blind us to the profound perceptions and wisdom, not to speak of untranslatable but nonetheless delectable delicacies of sound, sense and colour contained in the great artistic, literary and spiritual treasuries of mankind. Neither do Art and Literature deal merely with the true, the good and the beautiful. Quite often they chasten through terror and tragedy. Christ on his cross on Mount Calvary, and the stark and brutal setting of the profound colloquy on the battlefield of Kurukshetra, called the Bhavagad Gita (the Song of God) are the exemplars in spiritual literature. The Greek tragedies and those of Shakespeare, Goethe, Dante and Racine also come to mind.

The integrity of the scientists, the unflinching honesty and courage which they bring to bear on scientific enquiry of the material universe as it really is, and not as it might be, ate justly celebrated. “It is in the lonely places,” wrote HG Wells, “in jungles and mountains, in snows and fires, in the still observatories and silent laboratories, in those secret and dangerous places where life probes into life, it is there that the masters of the world, the rebel sons of Fate come into their own.”

Well said! But what is not equally celebrated, and not as justly, is the same unflinching honesty and courage with which men of the spirit, of Art and Literature have attempted to explore their equally infinite and fascinating dimensions of reality.

Looking at reality in the face, without flinching, is not the monopoly of the scientists. An ancient Indian scripture envisions the Lord of all existence as the universal Creator but also the universal Destroyer, of whom it can say in a ruthless image, “The sages and the heroes are his food, and death is the spice of his banquet.” The same scripture’s formula of the material world: “The eater eating is eaten” anticipated the Darwinian formulation millennia later that the struggle for life is the law of evolutionary existence. Also the Greek philosopher Heraclitus said: “War is the father of all things”. Modern science, it would appear, has only rephrased the truths.

However, wars in the days of Heraclitus, Krishna and Confucius were relatively minor affairs, and left largely untouched the lives of the non-combatants. Temples, monasteries, churches and homesteads were respectfully by-passed by the contending warriors. The nuclear arsenals at the disposal of the Big Powers make no such fine distinctions. The atom bombs which fell on Hiroshima and Nagasaki levelled all things sacred and profane. And those bombs were toys compared to the weaponry with which Andropov and Reagan attempt to frighten each other. Nuclear fission and fusion have rendered invalid the apothems of Heraclitus.

After all is said and done, science and technology are merely instrument in the hands of men. Instruments are neutral. No dagger or revolver has ever been charged in court with murder. It is the men who use them who are often charged, but alas, not always convicted.

Whether men and societies are malignant or benign is not determined by their science and technology. Modern technology can be programmed by men for either great construction or great destruction.

When assessing performance and consequences in the arts as well as in technology, we always come back to the qualitative elements in human education, motivations and perceptions. Not to dissect and separate the complex web of human life, but to bridge the gulfs between men, societies and cultures, and between the various disciplines in the sciences, arts and humanities, would appear to be the primary task of the leaders of society in all fields of endeavour. All parts are essential to the complete and effective ensemble. The artistic and religious impulses and intuitions are just as necessary to the total human and social make-up as science and technology.

If at all there is anything primary and basic, it is the common material foundation of both technology and the arts. Whether one wants to explore outer space or compose music and poetry, the launching pads must yet be fixed on solid old Earth. The good things of life, houses, computers, washing machines and the whole caboodle, require a foundation of material science and production. Neither can religion nor the other higher appetites of life thrive on empty bellies. Only bloody revolutions can flourish in conditions of material scarcity and of empty bellies.

Bread is therefore the universally acknowledged symbol of the material basis of human existence. And the bakers of bread are all those engaged in the processes of material production.

It bears repetition here that we cannot dissociate the quality of the bread from the quality of the bakers of bread. It took a poet, Kahlil Gibran, to remind us that “if you bake bread with indifference, you bake a bitter bread that feeds but half man’s hunger.”

In another simple but pregnant line, which captures both baker and bread in a single vision, the same poet summed up the significance of the work ethos thus:

“It is to charge all things you fashion with a breath of your own spirit.”

Life. And therefore my title: Bread is Beautiful. Let us all thank the good lord for our daily bread. And since we want good and wholesome bread, may He bless all bakers of bread, so that they may charge all things they fashion with the breaths of their own spirits.

——————–

Join IPS Commons’ Facebook page here.