Manpower Minister Josephine Teo announced during her Ministry’s budget debate this month that the tripartite labour partners — government, businesses and unions — have agreed that the retirement and re-employment ages in Singapore not only continue to be relevant, but should be increased.

The Minister also underlined that even as the retirement and re-employment ages are raised, the payout eligibility age for workers’ Central Provident Fund (CPF) accounts will remain unchanged at 65.

This will assure retiring cohorts that what they earn if they continue working will be on top of what they receive in CPF payouts when they reach 65.

Singapore’s CPF is a defined contribution system that does not reduce members’ payouts if they continue to work. This is unlike defined benefit systems in traditional welfare states like Denmark and Finland where pension payouts are reduced if the citizen has work income.

CPF monies are also exempt from tax both at the point of contribution and when paid out to members, in contrast to Scandinavian countries where pension income is also taxed as a form of earnings.

Both economic productivity and individuals’ retirement adequacy can be improved if workers are provided the support needed for them to remain in employment.

But this is challenging for Singapore. A bulge of baby boomers are confronting retirement-related milestones in their 60s, while their wages may not have kept up with cost of living and CPF minimum sum changes over the years.

How can we raise the new retirement and re-employment ages in a way that helps address the question of retirement adequacy, especially for those workers who are able and willing to continue working?

There are four age benchmarks of relevance here: 55 when some CPF monies can be withdrawn, 62 when re-employment kicks in, 65 when CPF payouts start for current cohorts and 67 when re-employment ends.

These four age benchmarks are somewhat arbitrary and historical, with age 55 being a “relic” from when the British created the CPF in 1953, 12 years before independence.

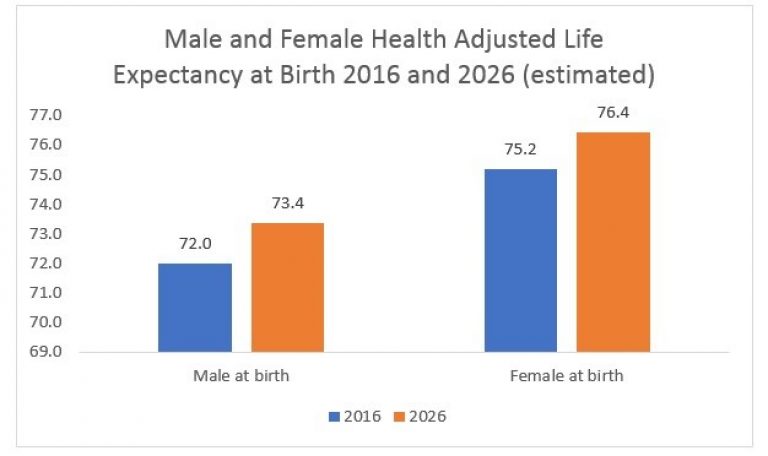

With improvements in healthcare, diet, and education, the estimated health-adjusted life expectancy (Hale) at birth is 72.0 and 75.2 years for men and women respectively in 2016. Hale is the number of years a person can expect to live in a healthy state on average.

First, we would propose raising the retirement and re-employment ages by three years to 65 and 70 respectively.

This will reduce confusion, as the retirement age will be similar to when workers can start receiving CPF payouts. At the same time, whilst the re-employment age shifts to 70, it keeps the five-year gap between the two ages.

This new and interim re-employment age would still be below, but closer to the Hale of 72 years for men in 2016.

In the longer term, however, the retirement and re-employment ages should be automatically benchmarked to improving Singaporean workers’ healthy life expectancy.

The last time the retirement and re-employment ages were raised in 2017, extensive consultations were also sought, with tripartite partners eventually deciding that both were relevant but needed to be raised. A tripartite workgroup has reached the same conclusion this time around.

But instead of having to convene workgroups every few years to update these ages, why not peg them to an effective proxy of workers’ ability to continue in employment such as Hale?

Cohorts born in 2026 would enjoy an increase of 1.2-1.4 years of additional health-adjusted life expectancy compared to those born decade earlier.

Estimates of Hale are derived from statistics on the disease burden and healthfulness (or otherwise) of the population by age and sex.

The Hale presented above reflects relevant trends in the labour force that are the result of successive generations enjoying improvements in preventive health and advances in medical treatment.

We can therefore peg the retirement and re-employment ages of cohorts retiring in say, 2026 to Hale in 2016, a 10-year lag.

This way, we can be sure that each cohort is already enjoying improvements in Hale before their retirement and re-employment ages are raised. This would mean that the re-employment age will be 72 in 2026, with subsequent adjustments made in tandem with the progression of Hale of Singaporeans with a 10-year lag.

In the unlikely event that Hale drops — meaning some of Singapore’s active ageing and social security trends would have reversed — then the re-employment age should be wound back down to reflect this setback.

Pegging retirement to life expectancy is not new, with countries such as Denmark having already started in 2006. Linking retirement to Hale has however not been tried anywhere in the world at this time, but it is a superior measure of the ability of the average worker to continue in productive employment.

Singapore’s indigenous labour pool is ageing, and within the next decade will begin shrinking if we remain anchored to outdated and fixed chronological age markers of one’s working lifespan.

Healthier and better educated older workers able and willing to contribute meaningfully to the workforce can be a powerful longevity dividend that can help Singapore redefine what it means to be old, and age successfully and with dignity.

This piece was first published in TODAY on 25 March 2019.

Christopher Gee is Senior Research Fellow and Damien Huang is Research Associate at the Institute of Policy Studies.

Top photo from Workforce Singapore Facebook.