By Elvin Ong

Electoral System Reform for a More Moderate and More Inclusive Singapore

On 23rd March 2013, The Straits Times published an article by ex-PAP MP Dr Ker Sin Tze, suggesting that Singapore can learn from the experiences of Hong Kong and Taiwan in attempting its own style of electoral system reform. On 27 March 2013, The Straits Times published forum letters from Devadas Krishnadas and Dr Jack Lee Tsen-Ta, Assistant Professor of the School of Law at Singapore Management University, both rejecting the idea that Singapore adopts a proportional representation system.

To make sense of the debate about electoral system reform, it is necessary to be clear about what electoral systems actually are, what electoral systems do, and examine the available empirical evidence of electoral systems throughout the world. Confusion about any aspects of electoral systems will likely lead to debates that generate more heat than light.

Electoral systems are formal rules that regulate the conversion of citizen vote choice into political representation. For parliamentary democracies such as Japan, Germany, New Zealand and the UK, this means converting votes into parliamentary seats in a single election. For presidential democracies such as Taiwan, South Korea and the US, it means converting votes into seats in the legislature, and for picking a president, in two separate ballots.

If we wish to build a more moderate and more inclusive Singapore – a country where the majority of Singaporeans can feel that their vote choices translate into meaningful political representation with adequate negotiation over public policy – then Singapore should seriously consider electoral system reform.

What Political Science Can Tell Us

Before I analyze Singapore’s current electoral system and look at ways in which it can be improved, it is useful to think about what the political science discipline has to say about electoral systems in general. Two characteristics of electoral systems stand out:

First, because electoral systems are the rules of the game as to how winners are picked amongst various candidates during elections, different electoral systems provide different incentives for politicians to develop different policies in order to win the most number of votes.

For instance, political scientists Frances Rosenbluth and Michael Thies studied the consequences of Japan’s electoral reforms in the early 1990s from a single non-transferable voting system to a mixed member electoral system. They suggested that the electoral system reform has lead to politicians and policymakers adopt neoliberal reforms to Japan’s political economy, thus generating benefits for Japan’s urban middle class.

Second, while specific electoral rules do not necessarily lead to certain outcomes, they make some outcomes more likely than others.

For example, the esteemed political scientist Arend Lijphart studied 36 democracies over two decades, which he divided between majoritarian and consensus democracies. He found that majoritarian democracies, which typically had majoritarian electoral systems, fared no better in macro-economic management of the economy as compared to consensus democracies, which typically had proportional representation electoral systems. In fact, consensus democracies are “high-quality democracies” that tend to generate “kindler, gentler” outcomes such as higher levels of female political representation, more equitable societies, better protect the environment, and put less people in jail.

In addition, and perhaps most importantly, he finds that “contrary to the conventional wisdom, there is no trade-off at all between governing effectiveness and high quality democracy – and hence no difficult decisions to be made on giving priority to one or the other objective.” (page 302)

Singapore’s Existing Electoral System

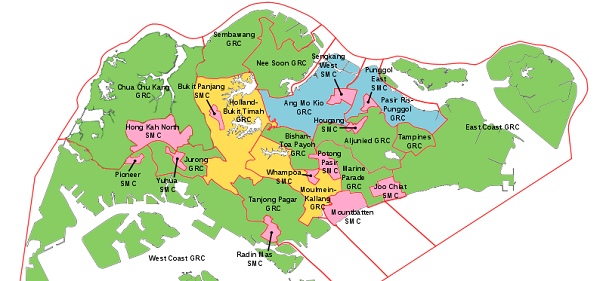

Singapore’s first-past-the-post electoral system, as it is today, is highly majoritarian. Whilst there are little qualms about the Single Member Constituencies (SMCs) and the “first-past-the-post” system, there are substantive problems with Group Representative Constituencies (GRCs). In a GRC, as long as a team of candidates win the majority of votes (say, for example, 55%), then the team sweeps all the seats for the entire district. Such an outcome has implications for both local and national levels of political representation.

At the local level, the 45% of Singaporeans in that particular GRC who voted for the losing team from another political party will feel alienated. Not only will they be bitter about voting for the losing team, they will have to contend with the fact that the winning team got four, five or even six representatives whereas they got none.

At the national level, the GRC system means that a simple majority in the popular vote can lead to a super majority of parliamentary seats. In the 2011 General Elections, the People’s Action Party won 60.1% of valid votes but 81 out of 87 (93.1%) of the contested seats. Thus, the voices of 33% of the population became “misrepresented” in parliament. That is one in three Singaporeans.

Not Too Hot and Not Too Cold

To be sure, as much as there are flaws for highly majoritarian electoral systems, we can expect there to be flaws for absolute proportional representation electoral systems as well. Small political parties that campaign on narrow issues can gain seats in parliament and propagate extremist views. Such views may polarize the public and lead to governance gridlock.

As with most issues, the trick is to find a delicate balance between both types of electoral systems so that we can ensure that parliament and its subsequent legislation is both moderate and inclusive. Many countries have realized the need for this, and have thus adopted mixed member electoral systems. These countries include Germany, New Zealand, Japan, and Taiwan, amongst many others.

In mixed member electoral systems, voters have two votes in an election. They first vote for the candidate whom they wish will represent their local electoral district. Then, they vote for a particular political party from a list of political parties whom they wish to represent their national interest. A specific number of seats in parliament will be allocated for political parties proportionally according to how many votes they obtained in the second party-list vote, subject to a minimum threshold.

For example, assuming that the minimum threshold for a party-list vote is 5%, if Party A won 45% of party-list votes, followed by Party B with 35% of votes, Party C with 15.5% of votes and Party D with 4.5% of votes, then a pre-allocated maximum number of 20 seats will be divided into Party A – 9 seats, Party B – 7 seats, Party C – 3 seats and Party D – no seats.

In Singapore’s context, the national party-list vote will replace the current Non-Constituency MP (NCMP) and Nominated MP (NMP) schemes. The members of parliaments for both schemes are currently beholden to the benevolence of the government-of-the-day, with the NMPs in particular being appointed after a nebulous, non-transparent interview with the government. Thus, they lack legitimacy from the Singaporean voters whom they purport to represent.

The final parliament envisioned will consist of both local electoral district and national party-list members of parliament, both of whom have equal voting rights in parliament. We can expect more robust debate and negotiation from the various political parties being represented in parliament, but not so much to the extent that effective governance is hampered.

At the end of the day, as Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong said in his 2011 National Day Rally Speech, in order to get both our policies and politics “right,” we must first “start with the politics.” Electoral system reform can help us generate a more moderate and more inclusive parliament, generating legislation and public policies that result in a more moderate and more inclusive Singapore.

—————–

Elvin Ong holds a Double Degree in Business Management and Social Science from Singapore Management University, and an MPhil in Politics (Comparative Government) from St Antony’s College, University of Oxford. His main research interest is in the mass politics of Southeast Asia, particularly Thailand, Malaysia, Philippines and Singapore.

——————

References

http://www.straitstimes.com/the-big-story/case-you-missed-it/story/picking-out-the-winners-electoral-systems-20130325

http://www.straitstimes.com/premium/forum-letters/story/changing-system-not-the-answer-20130327

http://www.straitstimes.com/premium/forum-letters/story/proportional-representation-has-its-limitations-20130327

Rosenbluth and Thies. 2010. Japan Transformed: Political Change and Economic Restructuring. http://press.princeton.edu/titles/9203.html

Arend Lijphart. 1999. Patterns of Democracy: Government Forms and Performance in Thirty-Six Countries. http://digamo.free.fr/lijphart99.pdf