Arun Mahizhnan –

Proponents of new technology tend to proclaim it as the revolutionary tool that would change the world; detractors respond with customary yawn. Arun Mahizhnan revisits the age-old debate.

In a recent, characteristically thought-provoking article, The Economist wrote about how Reformation leader Martin Luther “went viral” in the 16th century, half a millennium before the term became common code. On 31 October 1517, Luther nailed a copy of his protest dissertation, “95 Theses on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences”, which challenged the Catholic Church, to a church door in Wittenberg, Germany. His sympathisers took no time to exploit the then reigning new technology of the printing press to spread the word to thousands in Germany and elsewhere. Luther’s friend, Friedrich Myconius, reportedly said later that “hardly 14 days had passed when these propositions were known throughout Germany and within four weeks almost all of Christendom was familiar with them.” Hyperbolic perhaps but a testament to the basic fact of rapid circulation. In today’s parlance, Luther’s message had gone viral.

The Economist goes on to show the correlation between today’s cyber networks among citizens and the social networks of times past that forced religious reform in Europe.

The basic tale of a new communication technology “revolutionising” information sharing is as old as the hills. From conch shells, skin drums and smoke signals to the printing press, telegraph, television and the Internet, almost every new kind of information technology has had a significant effect on how people communicate and, invariably, how politics is conducted. Proponents of new technology tend to proclaim it as the revolutionary tool that would change the world; detractors respond with customary yawn.

Three samples:

Thomas Carlyle claimed in 1834 that “he who first shortened the labour of copyists by device of movable types was disbanding hired armies, and cashiering most kings and senates, and creating a whole new democratic world: he had invented the art of printing.”

Echoing Carlyle, historian Daniel Boorstin used pretty much the same words in 1978 to elevate television to the pedestal in his book The Republic of Technology by referring to “its power to disband armies, to cashier presidents, to create a whole new democratic world – democratic in ways never before imagined, even in America.”

More recently, in 1996, John Perry Barlow, an implacable advocate of Internet freedom, released a “Declaration of the Independence of the Cyberspace”. Among other things, he said: “I declare the global social space we are building to be naturally independent of the tyrannies you seek to impose on us. We are creating a world where anyone, anywhere may express his or her beliefs … without fear of being coerced into silence or conformity. We will spread ourselves across the Planet so that no one can arrest our thoughts.”

Go tell it to the Falun Gong, to the Iranian Green Movement, or to the newly minted North Korean supremo Kim Jong Un. Many sceptics hold that old rules still apply when it comes to controlling and suppressing the new media, and powerful governments and corporate interests will always trump the media freedom fighters. Really?

The Nature of the Beasts

Though it is tempting to devalue the power of any new technology, one has to examine its fundamental difference from the old ones in their nature and impact.

Old media such as newspaper, radio and television, and new media such as email, blog, SMS, Facebook and Twitter, are similar in that they reach out to the masses. How the latter engage and empower the masses is quite different.

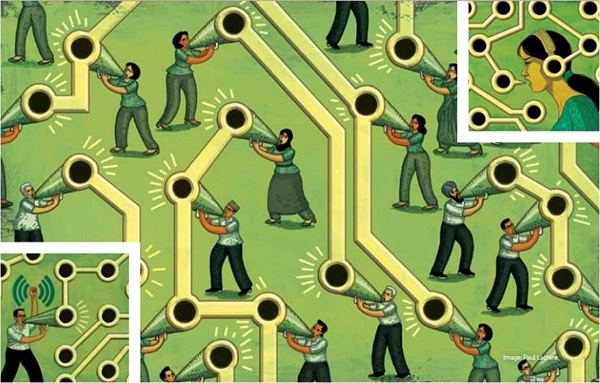

First, old media is defined by one-way communication – from producers of content to consumers of content. New media users are producers as well as consumers of content, sometimes called “prosumers”. Moreover, they deploy the same technology for one-to-one, one-to- many, many-to-one and many-to-many communications. A method of dissemination and consumption unmatched by old media.

Second, old media ownership required enormous capital investment, high level technological know-how, large workforce and, in most cases, permits to operate. Not so with the new media. Almost anyone can be a publisher or broadcaster online to reach big audiences – imagination and effort are all one needs – a facility unavailable through the old media. Third, old media almost always function as legal entities — identifiable and apprehensible. They have geographic and operational constraints that make them highly controllable by governments as well as by owners. With new media, no individual state or corporation can wield the degree of control they had over old media. It is instructive to note that while authoritarian states have managed to reduce the amount of political dissent in the old media, the same cannot be said of new media. In each of those countries, there is more political dissent in cyberspace now than in the past. Even in the strictest system, it is creeping in. Its flow can be regulated but not eliminated. This is where new media trumps old media.

Political mindscapes

So, what is the impact of new media on politics? Can old rules still apply?

First, the agency of the individual citizen is now vastly different. He/she can communicate and share information with fellow citizens on a scale and with a speed impossible before. More than information, the individual has a conversation, a critical improvement over old media communications. It leads to what in military jargon is called “shared awareness”, the ability of each member of a group to not only understand the situation at hand but also understand that everyone else does, too.

Social media enables citizen networks to enhance and increase shared awareness, allowing them to harness a potent force to mobilise and confront anyone from elected leaders to implacable tyrants. The ouster of Philippines President Joseph Estrada in 2001, with the help of mobile phone text messages, is often cited as the first instance of social media dethroning a reigning ruler. Ten years on, the more dramatic examples of the Arab Spring dominate such discourse.

Second, precisely because such citizen networks are not always founded on common causes or common views, nor centrally controlled or even coordinated, they have fundamental weaknesses and a high risk of failure. Outcomes of social network impact are often unpredictable, certainly not preordained. Juxtaposed against every Arab Spring triumph is a multitude of failures and fatal repercussions. Most recently, the Syrian government is ruthlessly hunting down political dissidents despite numerous social media initiatives to protect them. In recent memory, the Red Shirt uprising in Thailand saw much support in social media but was crushed by the military by conventional means. Far worse was the fate of the Green Movement in Iran in 2009, despite wide international support. For more than a decade, China has managed to exercise a stranglehold on the Falun Gong movement’s cyber networks — though unable to shut them down completely. Old rules or new rules, the political game is always unsettling and unsettled.

Third, legislation to control political dissent in new media is ultimately doomed to fail – though it may promise short-term successes. As mentioned earlier, almost all old media are legal entities and therefore lend themselves to legislative control — for good or evil purposes. The new forms of media proffer an altogether different proposition. Cyberspace being borderless, netizens respect no national boundaries. Besides, netizens could remain anonymous and untraceable to authorities.

Witness Wikileaks. This facility has upended the power ratio between the regulator and the regulated. Old rules of the old media can no longer function effectively in cyberspace. But even new rules by authoritarian states have far less effect than imagined. Some governments have taken to discreet neglect of those rules. Some others claim to exercise a soft touch out of benign disposition but that may be the only position open when a harsh touch may be impossible to execute or extract too high a political cost. Still, it is pertinent to point out that where common agendas prevail, such as the containment of child pornography and terrorism, collective actions by different states have been extraordinarily successful. Thus it takes a smart state to know when to apply what rules. Or even no rules.

Arun Mahizhnan is the deputy director of the Institute of Policy Studies. His email is arun.mahizhnan@nus.edu.sg .

The above article was first published on Global Is Asian, the publication of the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy.

Illustration by Paul Lachine for Global-is-Asian.

© Copyright 2012 National University of Singapore. All Rights Reserved. You are welcome to reproduce this material for non-commercial purposes and please ensure you cite the source when doing so.