Singaporeans are not replacing themselves.

This has led to concerns over workforce shrinkage and the impact of an ageing population on the economy. While liberal immigration policies were previously employed – and to a lesser extent, a more concerted approach than before to engage overseas Singaporeans through highlighting the merits of relocating back home – the government has had to deal with fall-out from this approach to immigration. Capacity issues on the housing market and transport fronts have influenced voting decisions, culminating in the People’s Action Party’s (PAP) worst showing in the 2011 general election since independence.

The Population White Paper in 2013 projected that Singapore’s population could expand to 6.9 million by 2030. Since then, other estimates of an “appropriate” upper limit have surfaced. At a public forum last month, former chief planner Liu Thai Ker cited a figure of 10 million and concurrently urged policymakers to plan beyond the 17-year ambit covered by the Population White Paper.

Beyond capacity constraints and political feasibility, an undermentioned aspect of population change is its impact on the welfare state and the well-being of the population. Such a discussion is timely amidst calls for a rethink of Singapore’s social compact and the balance between welfare provision and sustained prosperity.

Singapore’s Progressive Dilemma?

In 2004, journalist David Goodhart, inspired by British Conservative politician David Willetts, introduced the concept of the progressive dilemma, in which the trade-off for diversity was a supposed lack of social solidarity. This diversity, brought about by the onset of huge immigrant influxes, is said to result in less majority support for social programs that redistribute resources to those “unlike them”. Simply put, people may be less willing to contribute to state welfare as populations become more diverse.

As with most welfare models, it has been suggested the experiences of Denmark and Sweden in the coming years might shed more insights into the legitimacy of this claim. While both countries have high levels of redistribution, they do not share similar approaches to immigration, with 12% of Swedes foreign-born against the 6% of Danes. As Sweden continues to take in new immigrants, it will be interesting to note any impact on Swedish support for the welfare state. Parallels to such sentiments can already be drawn locally. There are Singaporeans who feel they have served National Service only to protect immigrants, who by extension are assumed to not have contributed as much as they have. Where should local policymakers look to for a road map to untangle the solidarity/diversity tension?

Professor Keith Banting from Queen’s University offers three lessons from the Canadian model of welfare. Firstly, an immigration policy prioritising migrants able to move into self-sufficiency has minimised the dependency they have on the existing social support structure, in turn, lessening the perception that they are a burden to existing tax payers. Secondly, he points to robust multicultural policies leading to the integration of a shared identity among all Canadians. Thirdly, Canada’s social programs are typically universal in nature, removing the risk of welfare initiatives being politicised by different entities.

Integration and the Rights Gap

Professor Banting’s second and third points deserve closer scrutiny. Policymakers here should keep tabs on the existence of the solidarity/diversity tension, and resolve the extent to which these differences determine how much welfare different groups receive.

They also need to resolve the tension between a guest worker system for foreign workers that is designed to limit their right to participate in local political and social life, and the need for greater integration in the face of widening inequalities.

In Southeast Asia, Singapore and Brunei are described as countries of destination, while countries such as the Philippines and Indonesia are largely ones of origin (Malaysia and Thailand have a mixed migration profile). Immigrant workers in Singapore are separated into the foreign talent/foreign worker dichotomy based on education, income, and work- sector differentials and, by extension, can come to be perceived as either potential citizen or transient worker. Foreign workers, unlike foreign talents, possess neither the market power nor the refuge of any political framework to ensure the security of their economic and social rights; this is reflected by how foreign domestic workers here are not covered under the Employment Act in Singapore, or how the state has floated the idea of housing foreign workers in nearby offshore islands. Immigration policies geared towards foreign talents, however, are more liberal and designed to fill critical sectors in the economy, especially the financial, creative, bioscience, and technological ones.

The denial of certain rights to foreign workers, consistent with the strategy of continuing temporary labour migration, runs contrary to the state narrative of integration. Public concern over a permanent underbelly of foreign workers compelled the Committee of Inquiry into the Little India Riot to address such concerns in their final report. Although they concluded that the riot was not caused by foreign worker dissatisfaction towards living conditions in Singapore, they conceded that there was room for improvement. Around a year prior to the Little India riots, SMRT bus drivers from China went on strike and refused to work, feeling they had no other recourse to protest unfair wages and poor living conditions.

Increasing legitimacy of alternative policymaking instruments

Measuring well-being has traditionally been done by asking people if they’ve achieved specific objectives in life, say knowledge, or if their basic needs have been met. Surveys that seek to flesh out “subjective well-being” to measure policy outcomes are now gaining prominence. The British Household Panel Survey, the World Happiness Report, and the World Values Survey now include questions on the emotions and sense of satisfaction that respondents feel about their lives.

The impact of population change on other aspects of purposeful living has been neglected. Beyond the infrastructural and density issues that characterise population growth in Singapore, many here are questioning if they can accept the scaling back of the economic priorities that drove liberal immigration policies. This would also be a test of policymakers’ resolve to cede economic measures of growth and to more precisely weigh other aspects of wellbeing when formulating public policy.

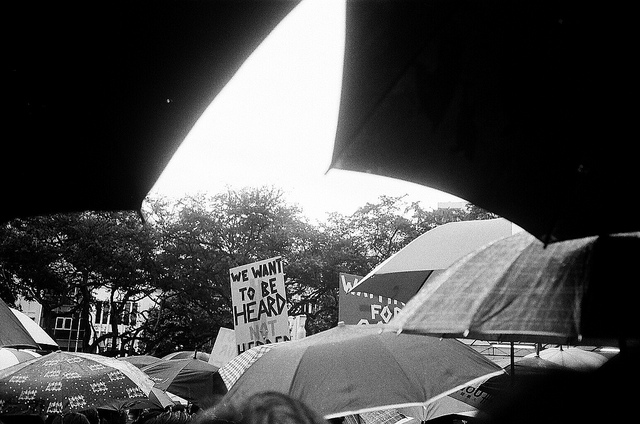

Even as more precise assessments of the infrastructural capacity to support a larger population are made, citizen preferences should be taken into account for future policy planning. People’s concerns over the size and make-up of the country’s population, their interest in welfare provision, and their pursuit of a sense of well-being reflect their aspirations in terms of the kind of society they want to live in.

Andrew Yeo is a graduate student at the London School of Economics. He is currently completing his Masters dissertation on Chinese perceptions of the Singaporean Identity.

Photo credit: Flickr