When news broke two weeks ago that athletes at December’s Asean Para Games would use the MRT to get from their lodging to the site of the meet, the media and other observers described it as an unconventional arrangement. They questioned if it would result in athletes with disabilities jostling with train commuters. Others pointed to how athletes at the SEA Games in June had been ferried around in air-conditioned buses.

The organising committee of the December Games said that the idea had been discussed with the Asean Para Sports Federation and the Singapore Disability Sports Council. Both bodies agreed that riding on the MRT would reduce travel time and promote “inclusiveness”, as athletes with disabilities and commuters would share a common space. The organisers later stressed that the athletes would be able to opt for shuttle buses and the MRT idea was not a “cost-saving” measure. Several athletes with disabilities also went on record to support the MRT plan.

Perhaps the organising committee had mistakenly prioritised the “inclusion agenda” over practicality and the needs of the athletes. The episode highlights then just how ill-defined the idea of inclusion is and why there should be more public deliberation about it. The motto, “Nothing about us without us”, has been used by the disability movement to remind policymakers and service providers that plans for inclusion, if not well thought out or implemented, can make individuals feel marginalised. It is, therefore, important for organisations, service providers and policymakers to actively consult people with disabilities when planning policies or arrangements that will affect their lives.

Research has shown that services that claim to be inclusive can be patronising or even oppressive. Some take a “tick-box approach” to arrive at this claim – they check off a list of general guidelines instead of asking how the constituents they want to serve will feel about the services offered

Researchers Eileen Hyder and Cathy Tissot studied a reading group started by a library in Britain, which positioned itself as “inclusive” as it catered to those with visual disabilities. They concluded that it was done merely to comply with a set of basic practices.

A participant who was interviewed as part of the study said: “I didn’t mean to be ungrateful to the volunteers but it’s the fact that they can do it ‘any old how’ and we should be grateful.” Other participants said that unlike other reading groups, they were not able to select the materials they wanted to read, and this made them feel excluded and marginalised. These feelings were exacerbated when they were not allowed to join other reading groups for the sighted.

Scholars of disability issues like Mr Paul Milner and Dr Berni Kelly have explained how inclusion can be potentially oppressive in ways that may not be obvious to the able-bodied. For example, chaperoning people with disabilities to highly public spaces is simplistic evidence of community participation – as it may come at the expense of their comfort or choice. People with disabilities may feel like they are being put under the spotlight when they may actually want to avoid unwanted public attention.

This raises the question whether service providers should assume that the “publicness” of the spaces and their level of visibility are important requirements for inclusion. If volunteers visit a special school, is this somehow considered less inclusive than if the special needs children are brought into a mainstream school or even just a public playground?

If so, this is doubly problematic. For it then assumes that “community” exists only in spaces that the majority occupies, and that mainstream settings are the only legitimate site for inclusion. Mr Milner and Dr Kelly argue that inclusion should also mean going into the spaces which are occupied by people with disabilities. They have challenged the “assumption that the path to social inclusion is unidirectional, involving people with disabilities making a journey to mainstream contexts without any expectation that non-disabled people need to make the return journey”.

Policymakers and service providers sometimes assume simplistically that inclusion is better than exclusion, and more of it is better than less. Yes, we need to accommodate people with disabilities openly and without pity. However, an inclusive social system is not one that simply seeks to include as much as possible, along all dimensions, across multiple contexts.

In fact, inclusion, and on the flip side, exclusion, are part of the larger social mechanism of classifying, sorting and understanding people. If we were to say that more inclusion is better under all conditions, then we are simply removing our ability to exercise discretion, discernment, and good judgment. The problem is not exclusion per se, but problematic exclusion, where people are discriminated against based on unsound or unfair criteria.

Therefore, the corollary is that we should not merely attempt to seek inclusion at all costs but to figure out what counts as sensible inclusion. Is legislating a compulsory quota for hiring people with disabilities a sensible way of ensuring economic inclusion or a problematic form of affirmative action? This requires figuring out what types and dimensions of inclusion should be encouraged, and under what conditions.

Few would disagree that society should encourage the increased participation of people with disabilities in socially expected roles. We should have more public conversations about how best to map out the intricacies of inclusion.

Justin Lee is a Research Fellow and Wong Fung Shing a Research Assistant at the IPS.

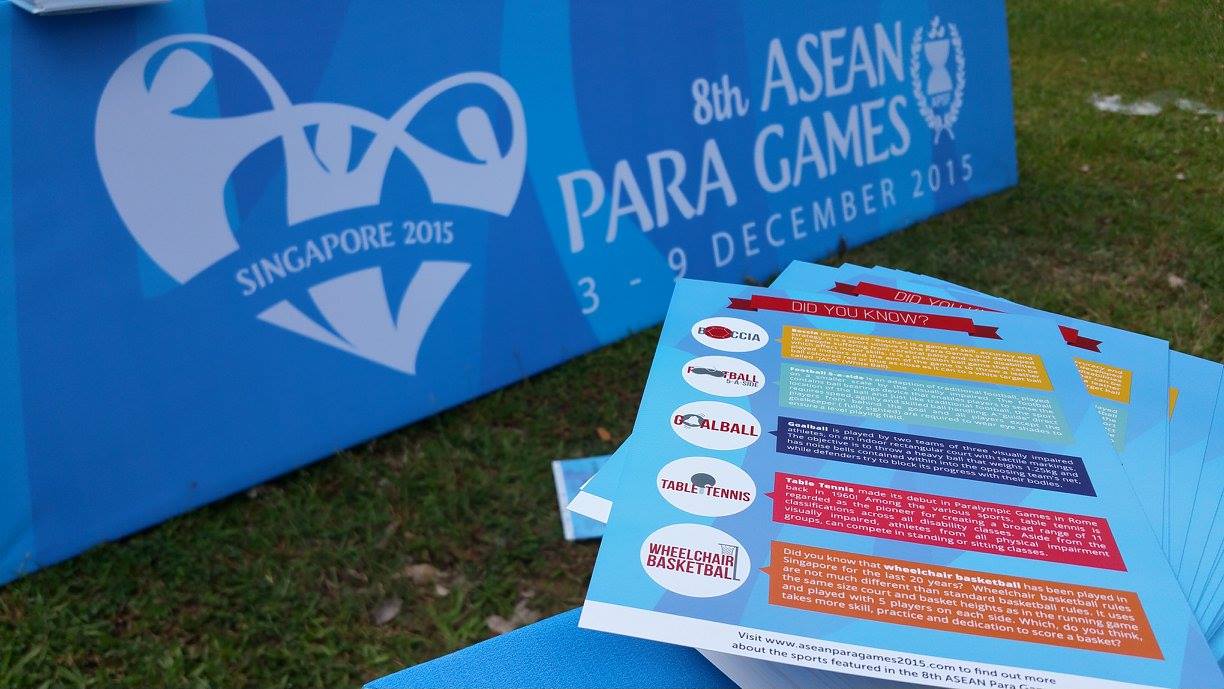

Top photo from ASEAN Para Games 2015 Facebook Page