By Donald Low and Cherian George

The Institute of Policy Studies has released three scenarios intended to get the wider public thinking about how Singapore should govern itself in the future. The exercise is timely, given the widespread feeling that the republic is at a crossroads. There is an opportunity to reshape governance, enabling it to respond more effectively to Singaporeans’ evolved expectations as well as the new challenges facing the country.

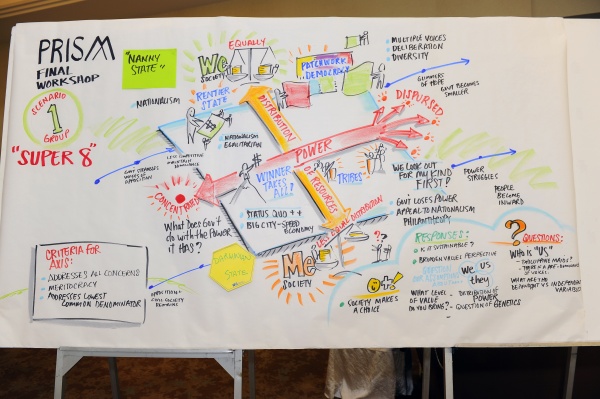

Along with more than a hundred other Singaporeans, both of us took part in the first phase of the IPS Prism exercise, which generated uninhibited discussion of the country’s politics, economy, society and culture. We hoped that the scenarios that IPS would develop would reflect this rich dialogue and catalyse further debate. The three scenarios released this week meet most of our expectations – but, perhaps inevitably, not all.

The point of any scenarios exercise is to force us to contemplate plausible futures, even if they are improbable or represent outcomes that we are uncomfortable thinking about. Good scenarios should not prescribe or foreswear any particular outcome; neither should they be overwhelmingly optimistic or pessimistic. Reality, including future reality, is likely to be a mix of the good, the bad and the ugly. Scenarios should try to capture and convey that complexity in vivid ways. Avoiding the extremes of Panglossian optimism and doomsday pessimism is therefore a cardinal rule that scenario planners swear by.

So what do we like about the Prism Scenarios? First, we like the three driving forces. These were the credibility of the government (or the extent to which it is trusted), how society defines success (whether in economic and non-economic terms), and the distribution of the rewards (winners or the rest). These three ideas capture quite well the central questions that a polity, any polity, asks of itself – questions of political trust and legitimacy, economic success, and social equity.

Second, the three scenarios are framed in a way that people can probably engage with. Whether intended for officials, chief executives or the man in the street, scenarios tend to connect when told through good stories (preferably with memorable titles). In this respect, the three IPS Prism scenarios are serviceable.

They convey and contrast the materialist and economic underpinnings of the Singapore state (SingaStore.com); the desire for a more equitable and just distribution of rewards (SingaGive.gov); and a model of governance that relies on the self-organising, collaborative instincts of citizens to meet their needs and collective goals (WikiCity.sg).

Each scenario also reflects a distinct tradition in governance and political theory. SingaStore.com reflects the political right’s emphasis on the primacy of growth, its faith in markets, and the prioritisation of narrowly economic goals over non-economic ones. Fans of Milton Friedman might be drawn to this scenario.

SingaGives.gov is broadly consistent with the political left’s vision of greater social justice and equity, and achieving social trust and solidarity through an activist, redistributive state. Think John Maynard Keynes.

The name WikiCity.sg conjures up images of well-functioning and self-organising forms of collaborative, deliberative democracies, such as those found in Switzerland and even Silicon Valley. In these places, government is often invisible. It is left to citizens and businesses – through collaborative platforms and institutions – to negotiate differences, find compromises and solve their collective action problems. The late Elinor Ostrom, who won a Nobel Prize in Economics in 2009 for her work on how communities deal with collective action problems without state interventions, is one of the patron saints of this perspective.

We ourselves consider this third scenario, WikiCity.sg, an extremely promising one for Singapore – but we find IPS Prism’s formulation of it limiting. As currently described, WikiCity.sg is portrayed in somewhat dystopian terms. It is as if “open source” government, as techies might call it, is worth considering only if you do not mind weak, paralysed coalition government that is “mired in gridlock” and suffers from a low level of trust.

It has certainly been the government’s position that Singapore requires a strong state and top-down consensus building, even at the expense of some individual rights. According to this view, a more pluralistic polity would erode the government’s ability to deliver the goods. Maintaining harmony in a diverse society like ours is only possible with a dominant state that mediates between the conflicting interests of citizens, so this theory goes.

The scenario as written is not implausible. If the government resists change and fails to adapt, the result could well be a broken system, forcing citizens to adopt the wiki-like approach of solving their own problems.

But we would suggest that a WikiCity.sg scenario need not be the outcome of a collapse of trust in public institutions and the resultant paralysis in government. It can instead be embraced as a positive vision for Singapore.

It is plausible for WikiCity.sg to be founded on the assumptions of high trust, and the ability of society to form consensus over difficult and thorny issues. No doubt, governance in WikiCity.sg is likely to be far messier – in the sense of involving many more participants whose views and interests are not easily streamlined. Quick decision-making would no longer be a privilege the government automatically enjoys.

However, this by no means implies a dystopian political future. What the government loses in speed, it can make up for in effectiveness, fidelity to the public interest, and a representation that better mirrors society’s diversity and pluralism. Indeed, many Prism participants other than ourselves had spoken in positive terms about government that is open and collaborative, even if necessarily messier.

Coincidentally, on the same day the Straits Times reported the IPS Prism scenarios, a page one story showed eloquently the power of open collaboration: a Singaporean amateur astronomer has helped NASA discover a new planet with four suns. This was made possible by NASA adopting an open-source approach to this and other major projects. This is not a sign of its decline (even if it may have been encouraged by budget cuts). On the contrary, NASA’s ability to tap talent – not only in-house but also by crowd-sourcing help from far and wide– may help preserve its dominance vis-à-vis the Europeans and the Chinese.

Similarly, more open, transparent and collaborative systems could foster greater innovation and resilience in the way Singapore governs itself. This idea should not be drowned by the PAP government’s dystopian scenario of paralysis, polarisation and weak government.

—————————-

Donald Low is a Senior Fellow at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, National University of Singapore. He previously served as the director of the Strategic Policy Office in the Public Service Division, where he was involved in a number of inter-agency scenario projects.

Cherian George is an Associate Professor at the Wee Kim Wee School of Communication and Information, Nanyang Technological University. He has written about “open source” government in his book, Freedom From The Press (National University of Singapore Press, 2012).

—————————–

—————

For reposting or use of any part of this article and images, please contact the editor (editor@ipscommons.sg) for permissions.

—————