“Is this your first visit to Pulau Penyengat?” the caretaker of a tomb asked while mopping the floor of the compound.

“Yes,” I replied.

“Ah! Now you can call yourself a proper Malay!” he chuckled.

I left the tomb momentarily confused.

About Pulau Penyengat

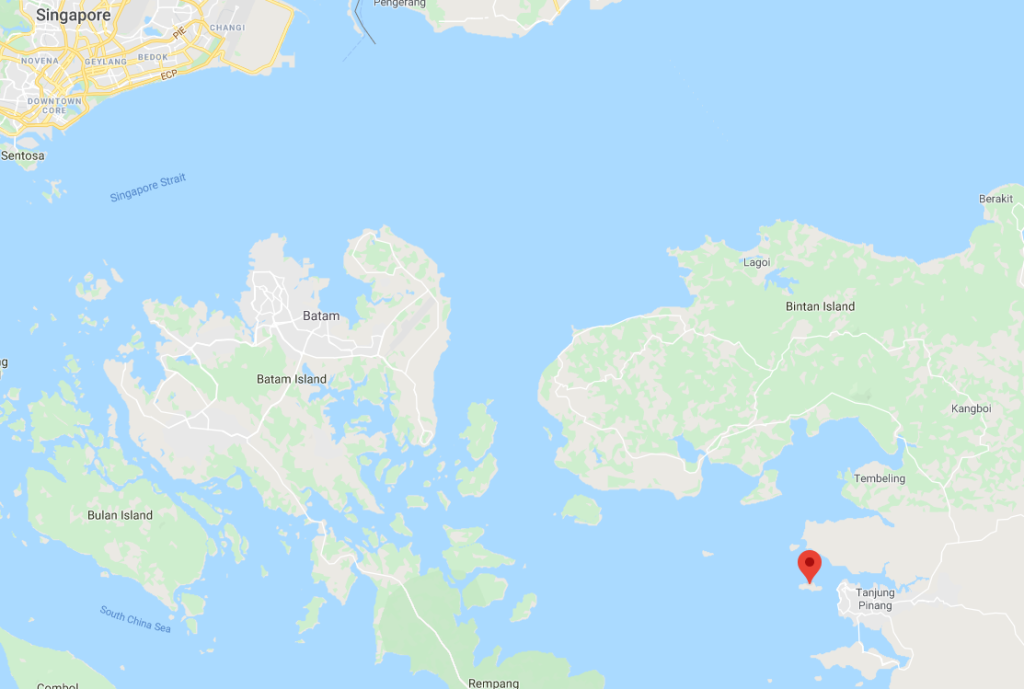

Located off Bintan and a mere 15-minute boat ride (aka pompong) from Tanjung Pinang, Pulau Penyengat (Penyengat Island) is located in the Riau Islands Province (Kepulauan Riau aka Kepri). It is a hidden treasure, and its significance to the shared history of the region is less-known to most Singaporeans. I too had not heard of this island until recently.

The location of Pulau Penyengat, off the coast of Bintan Island.

Being a self-proclaimed history junkie, I visited the island and found it to be an intriguing treasure chest of historical relics from the Riau-Lingga Sultanate, as well as a charming time capsule reminiscent of Singapore prior to the urban development, due to small roads, kampungs, wells and the lack of data connectivity.

Pulau Penyengat goes by many names. It literally translates to Stingers’ Island. In historical records, it was referred to Pulau Penyengat Indera Sakti. It was called Mars Island by the Dutch. By the locals, it was called Kota Gurindam (Poem City) as it was the birthplace of Gurindam 12 – iconic Malay literature written by Raja Ali Haji. The island was an intellectual base that attracted experts of various domains – literature, agriculture, astronomy, medicine, religion, politics – to the island for a chance to be a member of the Rusydiah Club, an exclusive intellectual club. The island was also called “Taman Penulis” or “Bustan al-Katibin” (Garden of Writers) as the writing scene was inclusive – transcending stations in life and genders. This meant that there are written works by princesses, fishermen and servants.

The island’s active intellectual scene and the presence of a powerful ruler led to the formalisation of the Malay culture. The first Malay dictionary that explains Malay grammar was written and published by royal lexicographer Raja Ali Haji. This standardised how Malay was spoken and used as a working and political language by Malay rulers, colonials, foreign traders and diplomats. It also shaped how Malay is spoken today and explained why Indonesia’s official language is Malay (Bahasa Indonesia) instead of the language of other ethnic groups. Additionally, the philosophy of the Malay culture was established on the island by scholars. A manner of speech, customs (adat), manners (adab), were also established by scholars and adopted and practised by Malay rulers and its people. The act of salam (kissing the hand of the elder as a form of greeting) and tunduk (lowering one’s body when one walks in front of an elder) are acts of respect still practiced by Malays today.

History

Before the Dutch invasion of Indonesia, the island was the administrative, cultural and intellectual centre of the Johore Empire which constitutes cities like Melaka and Singapore. It was also a fortress as it housed royal figures, administrative buildings, mosques, a royal library and a printing press.

Numerous historical events took place on the island. One of them was when Sultan Mahmud Shah II presented the island to his primary consort Engku Raja Hamidah, as dowry. The marriage strengthened ties between the Malays and the Bugis. However, it did not produce an heir to the throne. The Sultan’s heirs were Tengku Hussein Shah and Tengku Abdul Rahman, sons of his non-royal wives, who would later be embroiled in the succession dispute following his passing. The tombs of Engku Raja Hamidah and the non-royal wives are located on the island and open to visitors.

Tomb of Raja Hamidah, Raja Ahmad, Raja Ali Haji, Raja Abdullah & Raja Aisyah.

Present

The island is quiet on most days. Working adults choose to reside on neighbouring islands, elsewhere in Indonesia, or abroad for work and only return to the island (balik kampung) for events, functions and social gatherings — this is when the island comes to life. The people who reside on the island are young families whose children attend school on the island, those who are able to find work on the island and old folks in retirement (even then, some whom I spoke with told me that they live with their children off the island to take care of their grandchildren, but would occasionally return to maintain their properties).

While it has much history, one can easily organise a compact trip to the island. It takes a day to visit the sites. The sites include tombs, the Custom Hall (Balai Adat), forts, mosque, palaces and other ruins. The mosque and palaces may interest those who are keen on architecture and urban planning. For example, the Grand Mosque of the Sultan of Riau (aka Masjid Sultan or Masjid Raya) bear resemblance to Masjid Sultan in Kampong Glam and has a similar feature in its construction — both were built using egg whites. Also, Istana Tengku Bilik closely resembles Istana Kampong Glam (now the Malay Heritage Centre).

Grand Mosque of the Sultan of Riau

As I took the ferry back to Singapore, I now understood why there is a sense of Malay pride surrounding the island and its locals. The political, cultural, intellectual richness matches, if not, rivals, that of other civilisations. Sadly, for Singaporeans, this part of history has been eclipsed by decades of structured national history lessons and social and political injustices.

Amanina Hidayah is Research Assistant at the Institute of Policy Studies in Singapore.

This piece was first published on historyogi.org on 31 March 2020.

All photos from Amanina Hidayah.