Here’s a scenario that will be familiar to anyone teaching in higher education today. You’ve structured your course around take-home essays—those extended assignments that allow students to wrestle with complex ideas, consult multiple sources, and craft thoughtful arguments.

Then along comes ChatGPT, and suddenly half your class can deliver a passable essay on Kantian ethics or the causes of the Great Depression without reading a single page or thinking a single thought. What do you do?

Option A: Strictly prohibit AI use in student essay writing, while admitting under your breath that you have no reliable way of enforcing this rule.

Option B: Retreat to in-class exams that require students to write essays in a controlled, AI-free environment.

Option C: Abandon essay writing altogether, declaring it obsolete, and invent new assessments that require students to leverage AI tools.

Option D: Deploy some technological fix—such as mandatory drafting in Google Docs that lets you observe essays developing in real time—and hope that students don’t find a workaround.

While these represent the most common institutional responses to the AI-essay challenge, all are deeply unsatisfactory and represent a fundamental misunderstanding of both the nature of intelligence and the purpose of education.

Why Standard Solutions Don’t Work

Let’s start with the obvious: Prohibition simply doesn’t work when you can’t enforce it. Telling students not to use AI is like telling them not to think about pink elephants. The result is a two-tiered system where conscientious students follow the rules while the rest can cheat with impunity. This breeds cynicism and erodes trust in higher education.

Relying on technological safeguards for enforcement is also bound to fail. Once students discover workarounds to your safeguards—which they inevitably will—cheating will proliferate. The technological arms race between educators and students is not one that educators can win.

Retreating to in-class exams preserves the form of the essay but sacrifices its substance. The whole point of assigning essays is to give students time to think, research, synthesise and argue—cognitive processes that cannot and should not be rushed. An in-class essay is to real essay writing what speed dating is to marriage—it might look similar from a distance, but it’s missing everything that matters.

Abandoning essay writing might work for vocational courses where analytical writing was always peripheral. However, it’s not viable for most of the humanities and social sciences where the deep, higher-order, independent thinking involved in essay writing is essential to intellectual development.

Some argue that such intellectual work is obsolete; they say that AI will soon do much of our thinking for us and all that students need is training in how to outsource cognitive work to AI.

This simply gets it backwards. If AI becomes so sophisticated that it can handle all our deep thinking, then there’s no need for human workers trained merely as AI operators. Advanced AI systems would operate themselves more effectively than graduates with limited critical thinking skills.

In reality, those who excel at deep, independent thinking are precisely the ones best equipped to find creative, intelligent, and ethical ways of using whatever AI emerges. Students who focus on narrow, technical skills like ‘prompt engineering’ are the ones most likely to be outpaced as the technology evolves.

So, prohibition is naïve, abandonment is reckless, and retreating to in-class essay exams is shortsighted. Yet the essay is definitely worth saving. What is needed is a way of reconciling its pedagogical value with the reality of AI.

A Third Way: Intellectual Responsibility as the Guiding Principle

The mistake in current debates is the false choice between two extremes: all-out prohibition or uncritical embrace. Those who want prohibition don’t seem to understand that students can engage in deep, higher-order, independent thinking while using AI tools. For instance, a student might ask generative AI for critical feedback on their draft and judiciously use this feedback when making revisions. Other beneficial applications include copy editing, brainstorming when stuck, answering specific queries during the writing process, and converting detailed notes into fluent prose.

However, each of these can be misused in ways that undermine intellectual development. This then becomes the challenge: How do we enable students to use AI tools while preventing inappropriate use that would stunt their intellectual growth?

Many assume the solution involves detailed guidelines that meticulously catalogue all possible AI applications and specify when it is educationally appropriate to use them. But such an approach is doomed: it would be unwieldy, quickly outdated, and nearly impossible to enforce. Faculty would also disagree over what counts as ‘appropriate’, ensuring endless controversy.

I propose a different approach built on a simple, intuitive principle: Students must take intellectual responsibility for their work. This means that when you submit an essay, you should be able to explain and defend every significant choice you made—the thesis you advanced, the evidence you selected, the counterarguments you considered, the conclusions you drew. If you can’t explain why you structured your argument the way you did, or why you chose one interpretation over another, then you haven’t taken intellectual responsibility for your work.

This principle is both technology-agnostic and future-proof. It doesn’t matter whether a student used AI, or Wikipedia, or conversations with friends, or pure introspection. What matters is whether they can account for the intellectual decisions that went into their final product.

This approach has several advantages. First, it’s based on educational outcomes rather than technological policing. We care about whether students are learning to think, not whether they’re using particular tools. Second, it allows students to experiment with AI tools while maintaining educational integrity. Third, it focuses on something we can actually assess—whether students understand their own work.

But principles without enforcement mechanisms are just wishful thinking. How do we ensure that students actually take intellectual responsibility?

The Viva Solution

The answer lies in an assessment method that has been around for centuries but has fallen out of favour in modern higher education: the oral examination, or “viva”.

Here’s how it works. Students submit their essays as usual. I grade them normally, but while reading, I jot down questions: Why did you frame the problem this way rather than that way? What’s your response to this potential objection? How does your position relate to the broader scholarly conversation? Each student then comes to my office for a 15-minute conversation about their essay.

This isn’t an interrogation or a gotcha session. It’s a genuine intellectual conversation in which I’m trying to understand the student’s thinking. But it’s also a form of assessment. Students who can explain and defend their choices and demonstrate understanding of the complexities involved get high marks. Students who clearly don’t understand their own essays get very low marks.

The beauty of this system is that it makes AI-generated essays more trouble than they’re worth. A student who simply submits ChatGPT’s output might get a decent grade on the written component, but they’ll be exposed immediately in the oral component. The effort required to understand an AI-generated essay well enough to defend it convincingly is probably greater than the effort required to write the essay yourself.

Meanwhile, students who use AI as a thinking partner—who can explain how they engaged with the AI’s suggestions, what they accepted and what they rejected, how they moved beyond the AI’s initial offerings—will demonstrate exactly the kind of intellectual agency we want to cultivate.

Objections and Responses

Two objections are commonly raised to this approach. The first is that clever students will find ways to game the oral exam too. Perhaps they’ll use AI to anticipate possible questions and memorize scripted responses.

This worry strikes me as far-fetched for several reasons. First, there are too many possible questions for a student to prepare for all of them. Second, memorised responses sound different from spontaneous thinking, and any experienced teacher can tell the difference. Third, if a student did manage to prepare so thoroughly that they could demonstrate genuine understanding, they would have engaged in exactly the kind of deep learning that the assignment was designed to produce.

The second objection is practical: oral exams are time-consuming. A class of 40 students requires 10 hours of individual meetings. Given the already overwhelming demands on faculty time, this seems like an unrealistic burden.

This is a legitimate concern, but it reflects a deeper problem with how we think about education in the AI age. If we’re serious about preserving the kinds of learning that cannot be outsourced to AI, we need to invest in more intensive forms of instruction.

This might mean smaller class sizes, reduced teaching loads, or different approaches to curriculum design. These are institutional decisions that go beyond what individual faculty members can implement on their own.

But the investment is worthwhile. Universities are facing an existential question: If AI can complete the classwork we’ve been asking students to do, what value do we provide? The answer isn’t to become AI training centres, but to double down on what universities have always done best: developing independent, higher-order thinking. The deepest value of learning has never been information transfer or even skill acquisition, but the cultivation of human agency. The challenge is not to resist technological change, but to shape it in the service of cultivating our capacity to think, choose, and act with intention.

Matthew Hammerton is Associate Professor in Philosophy at the School of Social Sciences, Singapore Management University.

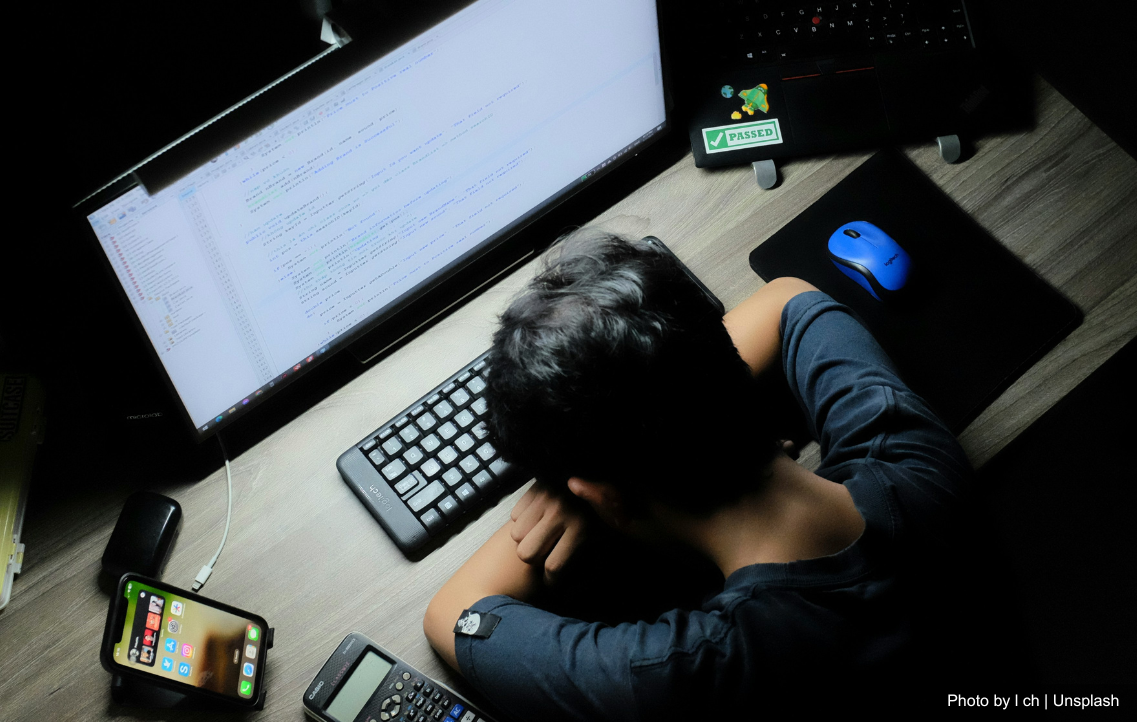

Top photo from Unsplash