The Eurasian Association (EA) recently launched an updated edition of its popular book, Singapore Eurasians: Memories, Hopes and Dreams. Edited by Myrna Braga-Blake, Ann Ebert-Oehlers, and Alexius A Pereira, the book chronicles Eurasian origins, community life and culture, and profiles Eurasians who have contributed significantly to Singapore’s history.

New chapters were added in this edition to showcase recent Eurasian contributions to the arts and sports, including Joseph Schooling’s historic Olympic gold medal.

Although a small community of approximately 15,000 people, out of a national population of 3.4 million, the Eurasians have punched above their weight.

Eurasians trace their origins to intermarriages between Europeans and Asians over the past few centuries. In those relationships, keeping to rigid boundaries of ethnicity would have been futile, since the very nature of intermarriages entails the dilution of any one set of ethnic markers and an intermingling of two cultures. In contemporary Singapore, a substantial proportion of Eurasians intermarry with other races, particularly the Chinese.

Children of these unions are racially classified based on their father’s race unless the couple chooses a double-barreled racial identity for their child.

Thus, one might ask why the Eurasians would want to continue to highlight and preserve their separate heritage and ethnic identity. Is assimilation into the dominant ethnic group not more realistic? Alternatively, Eurasians could completely ignore race categories, besides what is required administratively, and personally identify themselves as Singaporeans without a hyphenated race identity.

Some, such as Dr Alexius Pereira in his other book, argue that the recent attempts by Eurasians to preserve or, in fact, revitalise their ethnic identity, are due to the pervasiveness of the CMIO (Chinese, Malay, Indian, or Others) narrative of multiracialism in Singapore. Its framework compels individuals to find their identity as a member of one of the four groups: Chinese, Malay, Indian, or Others, to be fully Singaporeans. Each race is presented as having its distinct attributes — language, festivals, traditions and art forms, with little overlap with other races.

The Eurasians, however, do not possess some of these clear markers, given the diversity of their European and Asian ancestries. In earlier times, what had seemed common to them was their religious affiliation as Christians and their identification with English as their mother tongue. These markers, however, are increasingly less useful since many other Indians and Chinese are Christians, and a significant portion of Singaporeans use English as their primary language.

Many Eurasians began to feel that they were unrecognisable as a community, and perhaps did not have much of a distinctive culture — at least in the way it was conceptualised in Singapore.

By the 1990s, this had inspired the EA to narrate a unique official culture for Eurasians, one that could be consumed by both Eurasians and non-Eurasians alike. Such a culture, if it were to be accepted in the Singaporean context, had to look like how the Malay, Indian, and Chinese cultures were often depicted in Singapore, each having a language, cultural art forms, and celebrations.

The EA revitalised Kristang, the Portuguese-Malay patois, which — while hardly spoken in Singapore — was used among Eurasians of Portuguese descent in Malacca. They set out to popularise Eurasian cuisine, and created performable folk dances such as the Jingli Nona, which had dance moves and costumes inspired by Portuguese and Dutch cultural elements in Malacca and Macau.

Some elements of the now popularised Eurasian culture have little to do with bringing back the glories of Eurasian history, since they were seldom actually practised. Nonetheless, according to Dr Pereira in his book on Eurasians: “The accepted Eurasian culture today, as far as many Eurasians are concerned, serves its purpose. It allows Eurasians to feel like a complete member of Singapore’s ethnic mosaic.”

The pride that Eurasians feel in their identity and the comfort they seem to have found in their formally defined culture, even if some aspects of it were “produced” — a term used by Dr Pereira himself, who is also vice-president of the EA — underscores the fundamental place of ethnic identity in the Singaporean identity.

While Singaporeans hold national identity dearly, it is their ethnic identities, even if not fully performed, that keep them from cultural homelessness — the acute feeling that one’s experiences do not fit into any cultural reference group. In Singapore, national and ethnic identities are not mutually exclusive: The latter is an important constituent of the former.

Thus, we come full circle. In buttressing their distinctive identity, our Eurasians are ever more Singaporean. At the same time, by tradition, inclination, and necessity, the Eurasian identity is one that accepts other cultures and willingly incorporates features of other ethnic identities.

This openness to other cultures has been an intrinsic strength of the community, allowing them to contribute significantly in our national leadership during Singapore’s transition to independence, in international relations, and in the arts and media.

Through its ground-up efforts and Government support, the Eurasian community has successfully positioned itself as a clearly recognisable part of the CMIO framework. The community is not only featured in national events and celebrations but also collectively works to better the lives of Eurasians who may need that extra support.

It also remains open to recognising those of recent European and Asian parentage as New Eurasians, even if they might be racially classified differently.

There are other small but significant communities in Singapore, such as the Filipinos and the Myanmar people, who have had a substantially long presence in Singapore.

Their populations have grown in recent years as a result of immigration. Over time, it is likely that these communities, too, would want to define themselves with their unique culture and heritage as a recognisable part of the CMIO framework. Hopefully, these efforts will be appreciated by Singaporeans and not be viewed as attempts to undermine our cultural fabric.

The ability of smaller communities to celebrate their ethnic identity and be recognised as “legitimate” within the Singapore CMIO framework will serve to affirm the intrinsic elements of a dynamic Singapore identity: Openness and diversity.

Dr Mathew Mathews is a Senior Research Fellow from the Society and Identity cluster at the Institute of Policy Studies.

This piece first appeared in TODAY on 9 March 2017.

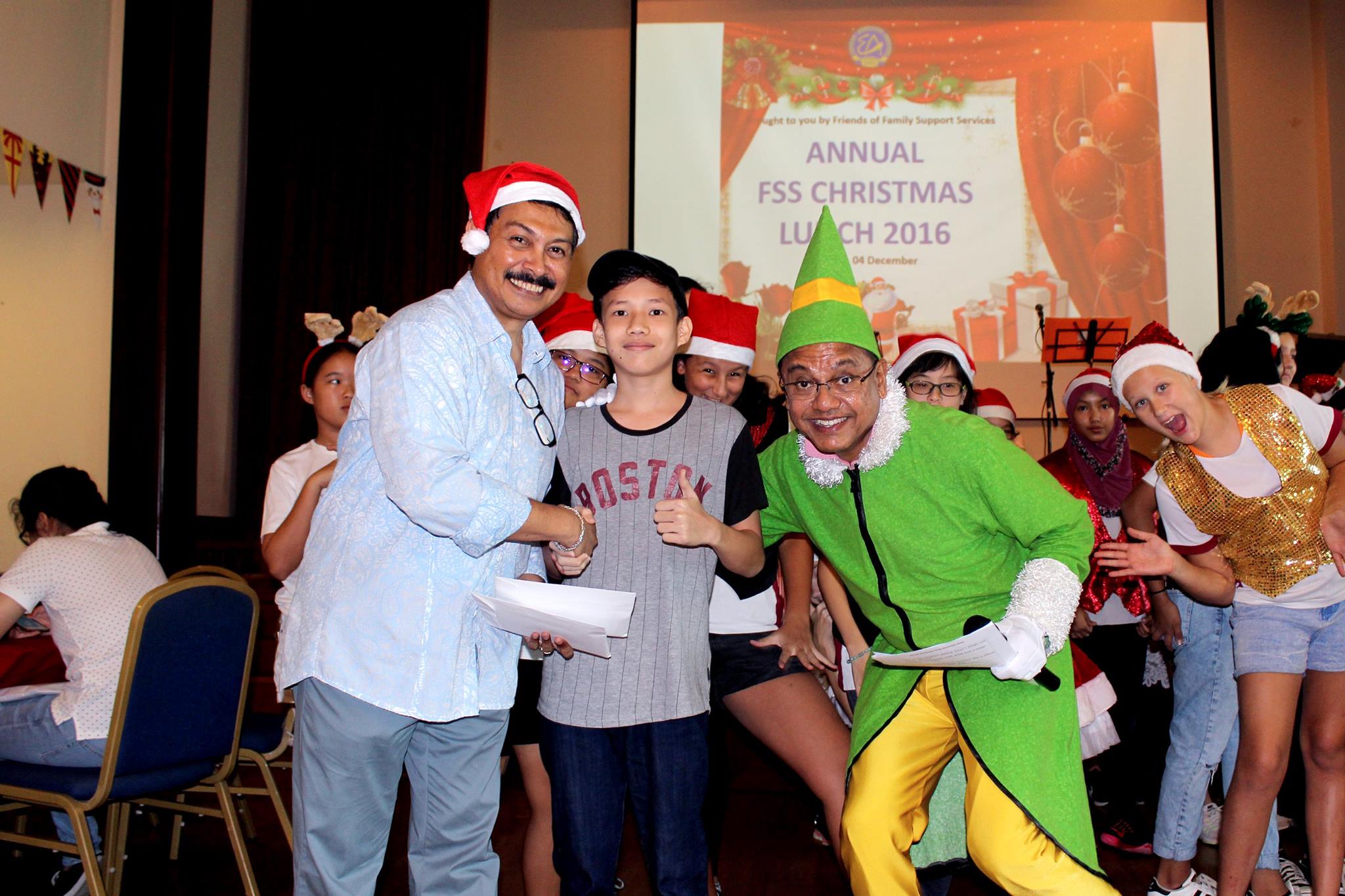

Top photo from The Eurasian Association’s Facebook page, at their annual Christmas lunch in December 2016.