Anyone examining election data from the past four presidential elections in Singapore would notice the absence of ethnic Malay candidates.

Since 1993, when the first presidential election was held, nine Chinese and three Indian men have applied to the Elections Committee for certificates of eligibility.

We have had three elected Presidents — the late Mr Ong Teng Cheong (1993 to 1999), the late Mr S R Nathan (1999 to 2011), and Dr Tony Tan Keng Yam (2011 to present). Only the late Mr Nathan did not face any contest for both his presidential terms.

At this point, the question that must be asked is: why have there been no ethnic Malay candidates in the past two decades?

One potential explanation may lie in entrenched “self-elimination”, which occurs when able candidates opt to withhold themselves from the process due to preconceived notions of their limited chances of success.

This phenomenon was first established in 1974 by sociologist Pierre Bourdieu. He warned against the dangers of continuous “symbolic domination” by an eminent group in a system. Over time, he said, non-dominant communities may unconsciously accept their position within society as a norm.

In the Singapore context, the prolonged absence of a president from certain minority races may result in capable contenders from these groups eliminating themselves from a contest or not even putting forward their candidacy, because they believe that the position is inherently “inaccessible”.

This state of affairs has undoubtedly informed the recommendations made by the Constitutional Commission to review the Elected Presidency.

In their 154-page report released by the government earlier this week, the Commission recommended safeguards in the elected presidency to not only ensure that the highest office in the land is accessible, but “is seen to be accessible…to all major racial communities in Singapore”.

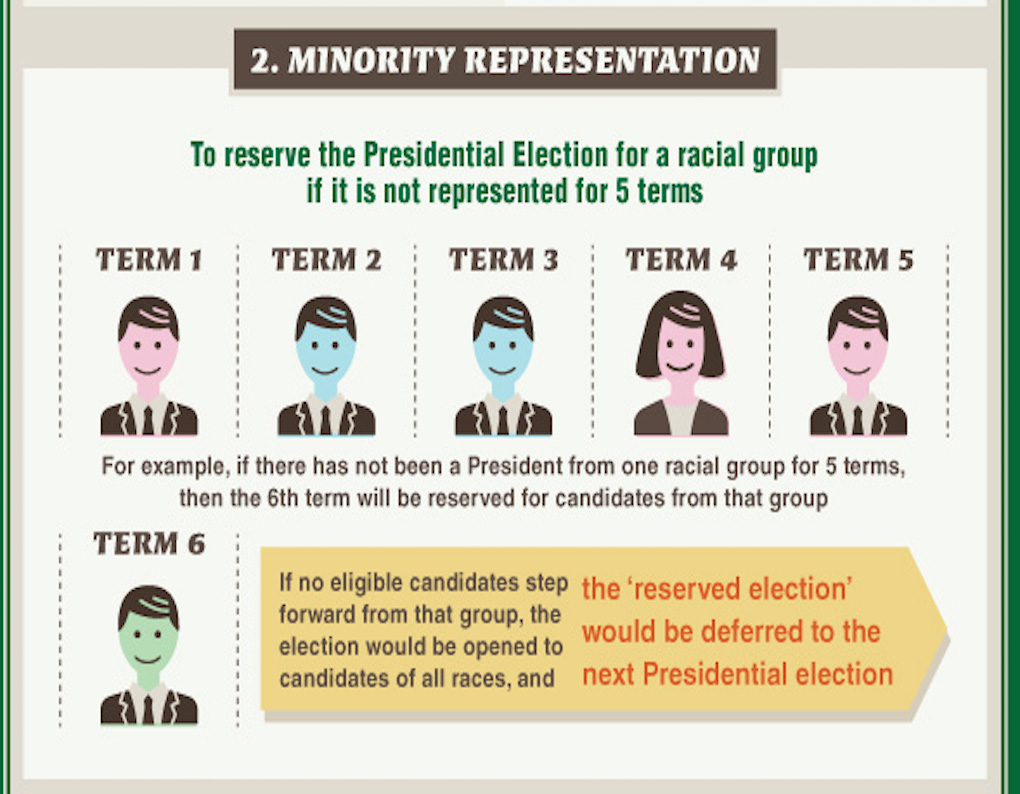

After careful consideration and public consultation, the Commission settled on the unique mechanism of a “reserved election” — an election reserved for a qualified candidate from a particular racial group in the event an elected president fails to surface from said community within five consecutive cycles.

This would ensure that the office of the Elected President is not dominated by any one racial group and more importantly, remains perceptually accessible to all, regardless of race.

Yet for all the optimism associated with the suggestion to have a reserved election, the consequences of this safeguard are equally worth pondering.

Analysts have cited the possibility of tactical voting, where a majority race may willingly choose to exploit the predetermined reservation as a justification to vote for candidates of their own race on the basis that they may be “locked out” in a coming cycle.

It also fails to address the bigger question, namely, the absence of specific minority candidates in the first place, a serious problem that should not simply be tackled by promoting ever more exclusive contests with the potential to emphasise racial divides instead of mending them.

In the last half-century, we have been able to successfully foster harmonious unity from an ethnic and religious diaspora. Our diversity reflects our strength as a people, but this strength cannot be taken for granted.

Thus instead of merely imposing engineered and directed solutions on a systemic level, we as a nation also need to address the heart of the issue. How can we foster an environment where candidates regardless of race are empowered to run for office? How can we continue to encourage unity and trust between Singaporeans, to aim for a state of affairs where race is a non-issue in elections?

Ng Zhong Wei is a second-year student reading Human, Social & Political Science at the University of Cambridge. He is currently an intern at IPS.

Top photo from The Constitutional Commission Report to review the Elected Presidency.