As an 18-year-old awaiting entry into university, I am not oblivious to my privileged position: I have the resources and opportunities for higher education and the ability to tap a myriad of information at my fingertips, and I live in a modern metropolis. With all these, surely all the doors to success and fulfilment are open to me.

Yet I am ambivalent about my future prospects. Perhaps others feel this way too. A report by Citi Foundation and the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) published last November, ranked Singaporean youths (between the ages of 13–25) 32nd out of 35 cities in terms of optimism about their economic future. Youth from places like London, Johannesburg and Chicago were relatively optimistic as compared to youth from Seoul and Hong Kong, who had similar feelings to those in Singapore.

This could seem counter-intuitive. In Singapore, we have the ability to attain paper qualifications, which are still seen as a means to ascend the socioeconomic ladder. In 2014, 42.4% of Singapore residents were either university graduates or had diploma and professional qualifications, up from 27.5% a decade ago. In 2015, it was reported that 20% of polytechnic diploma holders also secured a place in a university, up from 15% in the previous year.

But I would argue that our current pessimism is not unwarranted. Credential inflation and the knowledge that a more volatile and complex economy would require skills that we may not yet fully grasp, present a daunting future. And like past generations of young Singaporeans, we are trying to balance our ideals and post-materialist values within what is still a pragmatic and materialist society.

Credential inflation

Creeping credential inflation has eroded the conventionally-held belief of my parent’s generation that a basic university degree would be enough to secure an iron rice bowl. Thus, young Singaporeans have been called on to not just chase paper qualifications but to ground themselves in work-relevant skills.

There are indications that we are moving in that direction as vocational institutions start to gain popularity among youths. More have been seeking admission into local polytechnics over the past few years, especially into niche courses. Higher pay increases for Polytechnic diploma-holders signal better industry recognition of vocational education. This can bring about knock-on effects on the popularity of these institutions in the long run.

This parallels the situation in countries like Austria and Germany, where vocational schools are highly reputable. In Germany, the dual-education system provides teenagers with the opportunity to take up apprenticeships at firms where they can pick up relevant skills for their future careers. They obtain a small stipend for their work, but they also have to juggle their academic performance at the same time. This is a direction that Singaporean schools in the academic track can consider taking. Internships are mandatory for all if not most courses at the local polytechnics and the Institutes of Technical Education (ITE).

Balancing ideals with pragmatism

The “millennial generation” is beginning to acknowledge the economic trade-off in exchange for a healthier work-life balance, career mobility, and more avenues for expression of personal values through their work.

Like many of their counterparts around the world, an increasing number of young Singaporeans feel they will no longer be satiated by money alone. One of my friends is a strong academic performer who could, if he fulfils his potential, probably get a high-paying job in the corporate world eventually. He says his life goal though, is to teach students in lower-tiered schools and revamp the framework for community service in the local education system.

These ideals of doing good and changing society were present in earlier generations of youth — think of student movements throughout the decades premised on upholding justice, freedom and equity. But today, our developed economy status has brought about a corresponding shift into a climate where these ideals can be brought to the fore. Previously, ideals were either tempered by economic and social realities, or suppressed by the desperate imperative that drove many in my grandparents’ generation — the need to survive.

Perhaps those in the older generations are staring at us millennials in wonder. We are equipped to pursue our ideals; we no longer face the difficult ideological battles that made our national existence uncertain — capitalism or communism; peace or riots; bumiputera first or everyone equal.

And yet, the rising cost of living means that the realities of survival and income will continue to occupy our minds. We wonder if we will have to suppress our ideals for a sustainable livelihood. This engenders disillusionment and pessimism about the future.

American social scientist Ronald Inglehart, who developed the sociological theory of “post-materialism” — the transformation of individual values from ones based on materialism to those of autonomy and self-expression — posits that it would be convenient to identify either post-materialist or materialist goals as completely right or completely wrong, but this is impossible, as both are necessary for a healthy society. Is there any way then to provide the assurance to young Singaporeans of the year 2016 that marrying both idealism and pragmatism is possible? How can we strike this balance?

Where policy can help

Currently, young people in Singapore who want to pursue their ideals outside of academic qualifications — such as starting a business, going on an overseas expedition or embarking on a community service project — can get funding and capability-building help from both government and non-government organisations. The National Youth Council also supports youth development through training and other programmes.

But perhaps Singapore can consider putting together a coherent national youth policy, that brings together initiatives to both equip young people with skills for life and give them the means to articulate what it is that would make life fulfilling. Would that mean the development of a more caring, more inclusive society? A more open and free community? These questions could be explored from as early as a child’s primary school years, which is when their fundamental attitudes begin to shape up. The creation of a vision that they can work towards is a good starting point for this to happen.

What we have now are new initiatives in SkillsFuture, which include Enhanced Internships as well as an Individual Learning Portfolio (ILP) for individuals to discover their interests and abilities. These initiatives are crucial as the economy evolves. But they are still centred on skills and employment.

Perhaps some form of a social safety net for youths in Singapore can provide assurance to us young Singaporeans that chasing after ideals will not foreshadow falling off-track in pursuit of our pragmatic goals. Initiatives like the Prince’s Trust in the United Kingdom provide us a glimpse into how these safety nets can be strengthened – through establishing a strong support system that makes it possible for disillusioned youths to pick themselves up and better their lives.

Putting this in the Singaporean context could mean creating a stronger support system for youth whose projects have failed by re-investing in them, rather than to solely focus on having more youth starting their own ventures in the hopes that one strikes it big. There are a number of grants that help budding entrepreneurs to start a project they like if they are industrious enough, but these are usually granted to first-time entrepreneurs only.

The late Mr Lee Kuan Yew encouraged young Singaporeans to stop navel-gazing and “chase the rainbow”. At the end of the day, this chase for ideals is more than just a pursuit of self-expression but to effect greater public good in Singapore. But first, rising youth idealism needs to be given the space and opportunity to grow in tandem with the necessary but usual message about economic growth.

Ang Rae Ann completed her “A” Levels examinations last year and interned at the Politics and Governance research cluster of IPS till March.

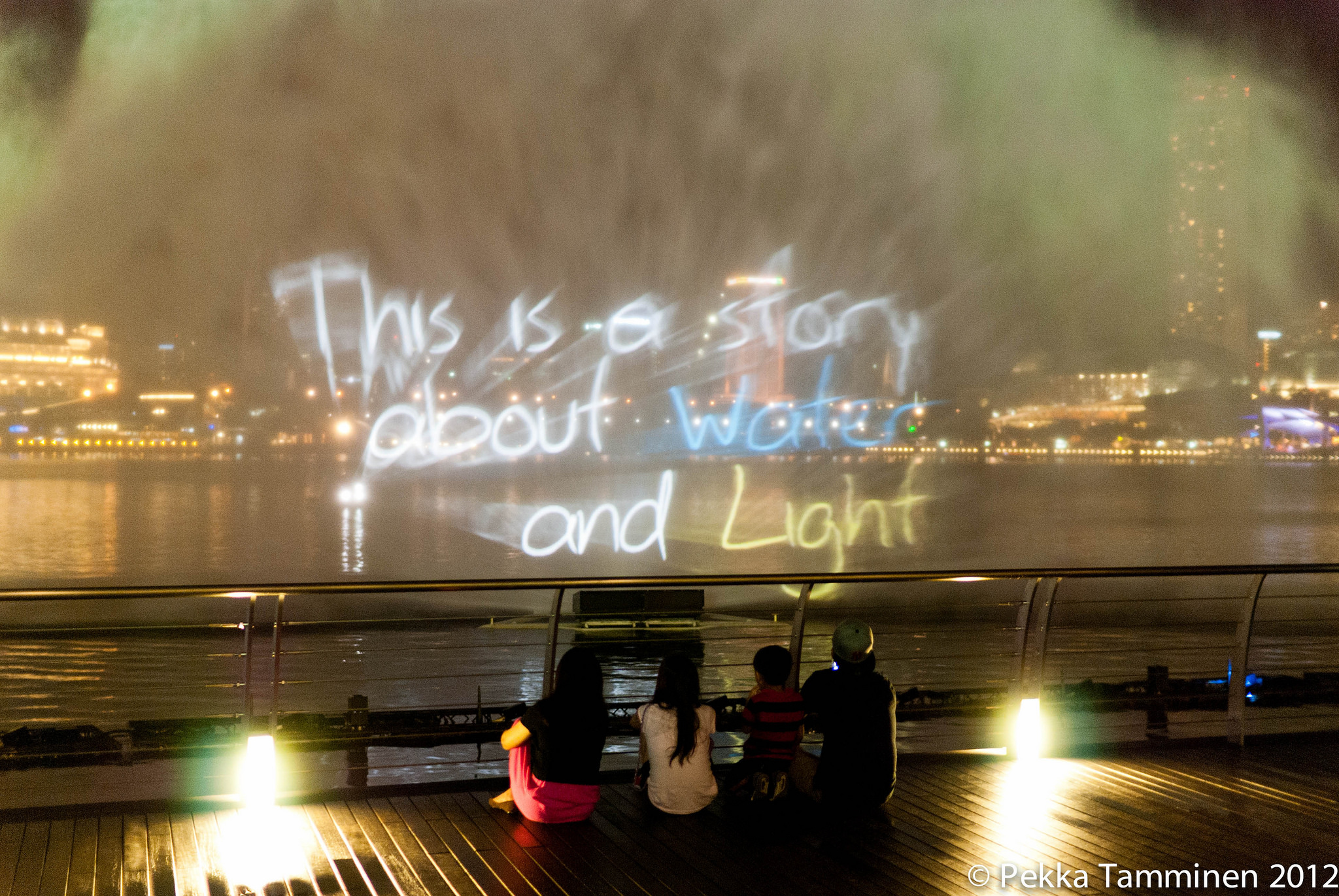

Top photo from Flickr | Pekka Tamminen.