Between January and September 2015, I interviewed 75 Singaporeans and did research on the issue of spoilt votes.

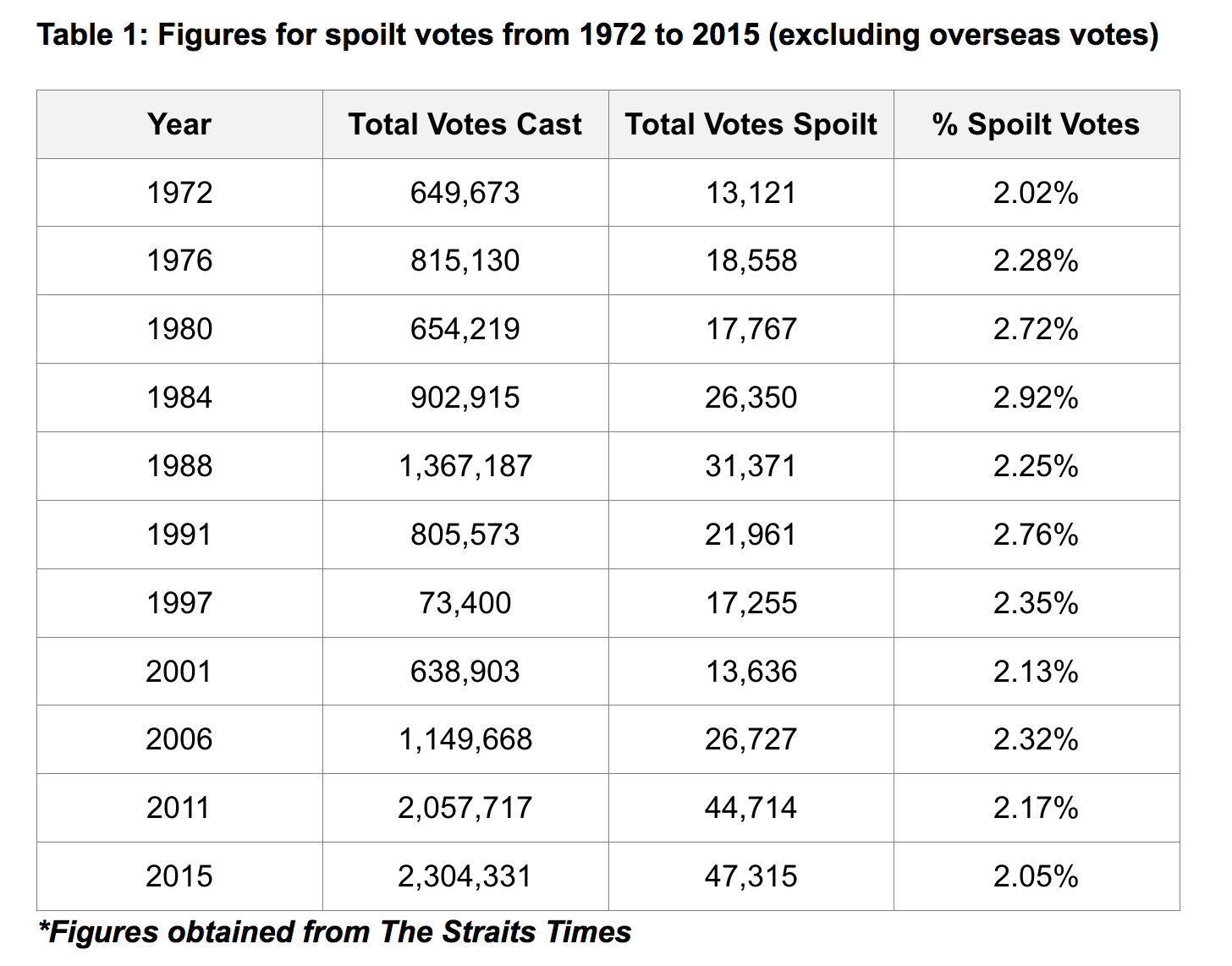

Spoilt votes — or ballots that are deformed such that they cannot be counted as valid votes — accounted for an average of 2.3% of all votes over the course of Singapore’s general elections from 1972 to the recent 2015 election. Analysts would be inclined to dismiss this figure as holding much analytical significance.

However, as illustrated in Table 1 below, although the percentage of spoilt votes has remained relatively constant, there seems to be a quantitative increase in the number of Singaporeans spoiling their vote.

What can we infer from this development? Through my interviews, I have concluded that spoilt votes — votes which are deliberately deformed, and not due to a lack of knowledge on how to vote, or simply an honest mistake — indicate general discontent with the socio-political status quo. It is therefore important to understand the signal that Singaporeans are sending by spoiling their ballot at the polls.

Voting is mandatory for all Singaporeans aged 21 and older, and deliberate vote spoilage is regarded by many as a legitimate way to express unhappiness and dissatisfaction.

Those I interviewed — not all of whom spoilt their vote — said they viewed vote spoilage as both a protest against the incumbent PAP regime’s approach towards governance and a vote of no-confidence for the opposition parties contesting in a particular constituency. That is to say that while they did not want to support the PAP team in their constituency, neither were they enamoured of the opposition team, who they did not find to be credible.

A small poll I conducted through my interviews with the 75 Singaporeans led me to conclude that the definition of a credible opposition is one that is able to stand ready as an alternative government, capable of offering substantial and sound long-term policy alternatives, as opposed to mere lip-service and empty promises.

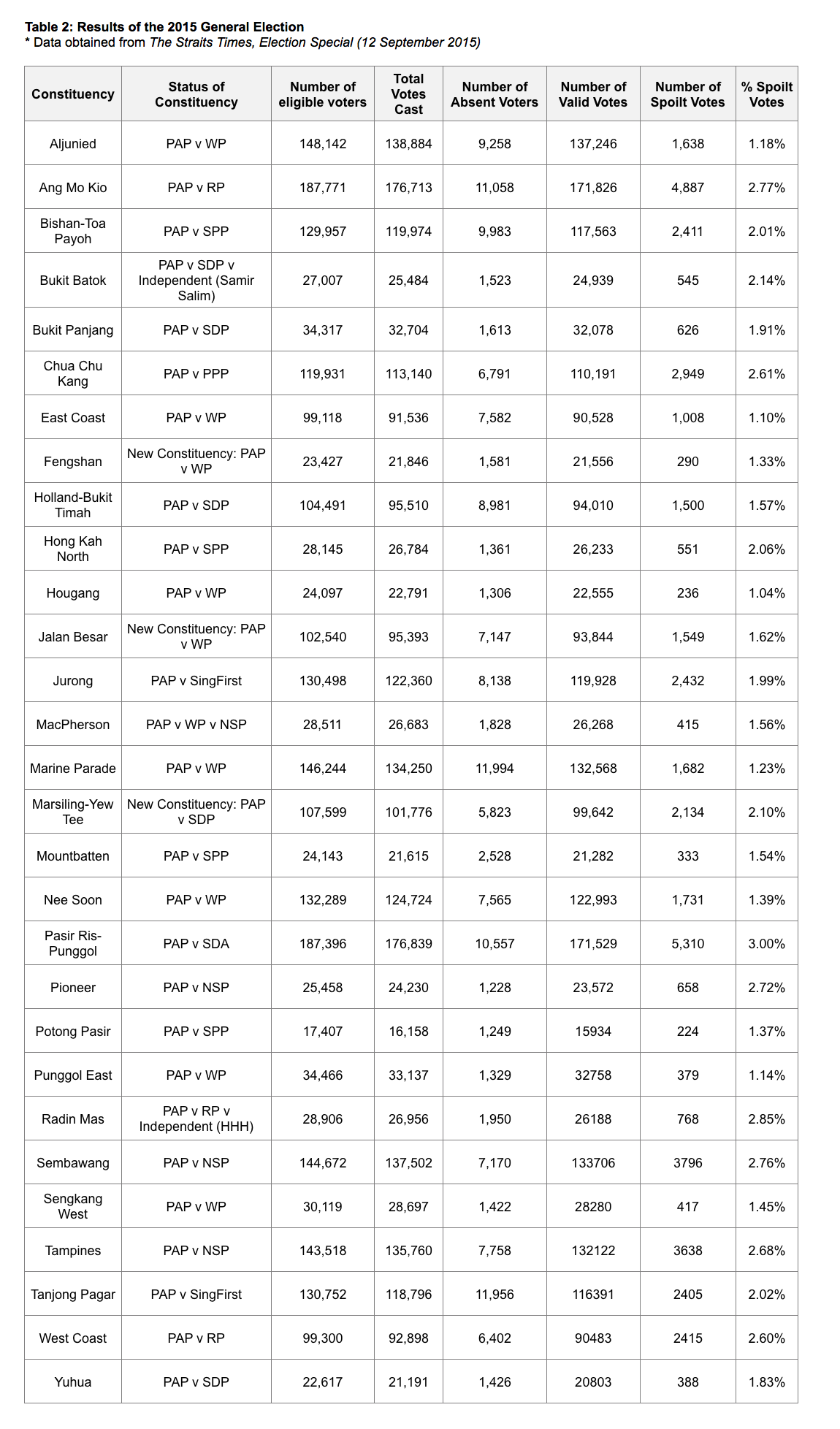

I have also observed an inverse correlation between the percentage of spoilt votes and the strength of the opposition parties contesting in any particular constituency. In other words, the more credible the opposition party seems, the lower the percentage of spoilt votes.

The results of the 2015 General Election have been included for easy reference in Table 2 below. This voting pattern suggests that the Workers’ Party (WP) — which is seen as the most credible alternative to the PAP — does enjoy the support of Singaporeans vis-à-vis other opposition groups and independent candidates.

In contrast, where the opposition team is viewed as less credible, say the National Solidarity Party (NSP), and there is a straight-fight with the PAP, the spoilt vote percentage is higher. This can be seen in Pioneer SMC (2.72%); Sembawang GRC (2.76%) and Tampines (2.68%).

Based on my study, political apathy and ignorance could be other factors causing Singaporeans to spoil their ballots — though this proportion of the electorate is arguably decreasing given the advent of alternative media platforms and social media.

In the 2015 election campaign, an individual could attend any rally virtually and keep up-to-date with real-time updates through Twitter feeds and Facebook posts. Additionally, the ability for individuals to post instantaneous comments and responses on these social media sites has resulted in an increase in political participation and awareness. Like-minded individuals who are disgruntled by the shortcomings of a particular policy would be able to identify each other and display their collective discontentment through various means.

However, despite this increase in political awareness, a resident and election official for the 2006 and 2011 elections living in Ang Mo Kio GRC told me that Singaporeans who “don’t know who to vote for…will just spoil their vote, since voting is compulsory”.

A third and emerging phenomenon that surfaced in my research on why people spoil their votes is the role of familial and social networks in attempting to socialise individuals to adopt and support a particular political ideology.

Once regarded as a sensitive issue, politics now dominates dinner table conversations and coffee-shop talk. Bombarded with differing opinions of the political landscape, individuals may become overwhelmed by the overload of information. Frustrated, these individuals may choose to spoil their vote, remaining indifferent to the electoral outcome so long as they assume that they can carry on with the life they are accustomed to. Several voters from Ang Mo Kio GRC told me that there were too many differing views to rationally make sense of all the political developments. One voter further articulated the dilemma as such: “It is difficult to make an independent and informed choice, hence spoiling votes is seen as the best way to comply with compulsory voting”.

In sum, the act of spoiling one’s vote serves as a legitimate form and primary means of registering discontentment towards the parties contesting the general election. However, this is not the only means to articulate discontent towards the political options voters are confronted with.

Alternative forms of political protest and articulating discontent apart from the vote or spoiling one’s vote would include the attendance at opposition rallies, and the use of social media platforms to exchange ideas and identify other people with similar angst. This increase in political awareness and local involvement with politics would translate into popular support to push for substantive attitudinal and policy changes from the incumbent PAP regime as well as to keep the opposition on their toes as a viable political alternative to the PAP.

Jeremy Ho is a final-year political science undergraduate at NUS. This is an excerpt of his paper: “Spoilt Votes in Singapore’s Electoral Politics: Understanding the Causes and Impacts of Spoilt Electoral Votes in Singaporean Politics” which was submitted as an independent study and research paper for the University Scholars’ Programme.

Top image from ELD print advertorial on polling day 2015